Prof. Dr. Thomas Bohn of the Justig Liebig University in Giessen, Germany, who has previously published a few papers on vampires and co-edited the third volume of Corpus Draculianum, has written a book on vampires that is set to be published this April by Böhlau Verlag: Der Vampir: Ein europäischer Mythos (The Vampire: A European Myth).

According to the publishers, Bohn follows the metamorphoses of the vampire and succeeds in rehabilitation the vampire as a European myth:

'In nahezu allen Epochen und Kulturen hat es Geschichten von Wiedergängern gegeben, die nach dem Tode ihr Unwesen treiben, oder von unheimlichen Blutsaugern, die nachts aus ihren Gräbern steigen und sich ihre Opfer unter den Lebenden suchen. Wie alle Mythen verändern sich auch Vampirgeschichten stetig und passen sich dem Zeitgeist an. So gilt seit dem Erscheinen des Dracula-Romans beispielsweise Transsilvanien, das „Land jenseits des Waldes“, irrtümlich als die Heimat der Vampire.

Thomas Bohn hat sich mit den Fragen, wann und weshalb das östliche Europa zum Refugium der Blutsauger stilisiert wurde, auf die Suche nach den Ursprüngen des Vampirismus gemacht. Der Osteuropahistoriker folgt den Metamorphosen des Vampirs, indem er die Angst der kleinen Leute vor den Seuchenherden aufgeblähter Leichen von der Blutsaugermetapher der Gelehrten unterscheidet. Seine Reise in die Vergangenheit zeigt, dass das Bild des Blutsaugens im lateinischen Abendland lange vor der Entdeckung der Vampire im Donau-Balkan-Raum geprägt wurde. In diesem Sinne rehabilitiert dieses kenntnisreiche Buch den Vampir als einen europäischen Mythos.'

Magia Posthuma

On several occasions, particularly on the periphery of the Habsburg Empire during the 17th and 18th centuries, dead people were suspected of being revenants or vampires, and consequently dug up and destroyed. Some contemporary authors named this phenomenon Magia Posthuma. This blog is dedicated to understanding what happened and why.

Sunday, 7 February 2016

Sunday, 25 October 2015

After 135 years: Sava Savanovic in English

Although so many pieces of vampire fiction have been compiled and published over the past decades, Serb author Milovan Glišić’s Posle devedest godina (After 90 years), originally published in 1880, has remained elusive to readers outside of the Balkans. Until now that James Lyon, author of The Kiss of the Butterfly, has translated it into English.

Obviously, the story is from an era when authors took a particular interest in translating local folklore and etnography into fiction, and reading it reminds me vaguely of the local Danish variant of The Wise Men of Gotham, those humorous stories of foolish and incredulous people inhabiting some backwards countryside. Essentially, After 90 Years is a love story with one village stealing a bride from another village (you know, not dissimilar to Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, but on a lesser scale), that mixes in a vampire story and a lot of etnographic detail.

The vampire, the well-known Sava Savanovic that made the headlines a few years ago, haunts a watermill in Zarozje, so it has become impossible to hire a miller, for no one survives a single night in the mill: 'At dusk he was hale and whole, and at daybreak dead, with a red bruise around his neck as though strangled with a cord.' Savanovic himself appears 'with a face as red as blood', carrying 'across his shoulders a linen shroud that dropped down his back all the way to his heels,' for as Lyon says in a footnote: 'In South Slav folklore, a vampire’s power resides in its burial shroud, which it typically wears draped around its neck and shoulders. If the vampire loses this shroud, then it loses any special powers.'

It is certainly nice to finally read the story, which as a vampire story benefits from the author's wish to rely on the actual folklore instead of employing literary conventions of the type familiar from other nineteenth century vampire stories like e.g. Aleksey Tolstoy's The Family of the Vourdalak.

Andrew M. Boylan, known for his quest to watch and review any film related to vampires, supplies a foreword that explores the relationship between the story and the film adaptation, Leptirica, and Lyon himself writes about the translation, Zarozje and vampires.

Andrew M. Boylan, known for his quest to watch and review any film related to vampires, supplies a foreword that explores the relationship between the story and the film adaptation, Leptirica, and Lyon himself writes about the translation, Zarozje and vampires.

Available as both a paperback and an e-book at a reasonable price, After 90 Years is worth seeking out.

Speaking of James Lyon, I would also recommend a book that has nothing to do with vampires - although he does actually mention Vlad Tepes in it: Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War, the history of the complex political and military events on the Balkan Front before and after the outbreak of the first World War.

Obviously, the story is from an era when authors took a particular interest in translating local folklore and etnography into fiction, and reading it reminds me vaguely of the local Danish variant of The Wise Men of Gotham, those humorous stories of foolish and incredulous people inhabiting some backwards countryside. Essentially, After 90 Years is a love story with one village stealing a bride from another village (you know, not dissimilar to Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, but on a lesser scale), that mixes in a vampire story and a lot of etnographic detail.

The vampire, the well-known Sava Savanovic that made the headlines a few years ago, haunts a watermill in Zarozje, so it has become impossible to hire a miller, for no one survives a single night in the mill: 'At dusk he was hale and whole, and at daybreak dead, with a red bruise around his neck as though strangled with a cord.' Savanovic himself appears 'with a face as red as blood', carrying 'across his shoulders a linen shroud that dropped down his back all the way to his heels,' for as Lyon says in a footnote: 'In South Slav folklore, a vampire’s power resides in its burial shroud, which it typically wears draped around its neck and shoulders. If the vampire loses this shroud, then it loses any special powers.'

It is certainly nice to finally read the story, which as a vampire story benefits from the author's wish to rely on the actual folklore instead of employing literary conventions of the type familiar from other nineteenth century vampire stories like e.g. Aleksey Tolstoy's The Family of the Vourdalak.

Andrew M. Boylan, known for his quest to watch and review any film related to vampires, supplies a foreword that explores the relationship between the story and the film adaptation, Leptirica, and Lyon himself writes about the translation, Zarozje and vampires.

Andrew M. Boylan, known for his quest to watch and review any film related to vampires, supplies a foreword that explores the relationship between the story and the film adaptation, Leptirica, and Lyon himself writes about the translation, Zarozje and vampires.Available as both a paperback and an e-book at a reasonable price, After 90 Years is worth seeking out.

Speaking of James Lyon, I would also recommend a book that has nothing to do with vampires - although he does actually mention Vlad Tepes in it: Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War, the history of the complex political and military events on the Balkan Front before and after the outbreak of the first World War.

Saturday, 3 January 2015

A disinterested appraisal of Summers-ism

Back in 2011, I wrote two posts on ’a critical edition’ of Montague Summers’s The Vampire: His Kith and Kin edited by John Edgar Browning: A sustained study in projection and A Delayed Demonologist. These posts allowed me to once and for all collect some of the assessments that have been made of Summers’s work on ’the subject of witchcraft’, which includes the books on vampires and werewolves.

Recently, The Apocryphile Press has published The Vampire in Europe: A Critical Edition, once again edited by Browning, who in his preface remarks on the mission of these critical editions: ’Our approach, as literary critic Maurice Hindle noted after the fact, was instead a ”disinterested appraisal,” one aimed at re-visiting a familiar yet widely unexplored work with renewed perspective and interest in order that we may situate the book and its author in their historical context.’

I think that I have stated my mind on the matter in the aforementioned posts, but I am also happy to note that the new book does in fact include voices that comment on the style and contents of Summers’s work, because Browning has included excerpts from original reviews of The Vampire in Europe, both from 1929 when it was originally published and from 1960 onwards when it was reprinted.

Thus, according to a reviewer in The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer on November 27, 1929, Summers’s ’new book, like its predecessor, ”The Vampire: His Kith and Kin,” reveals an astonishing learning hand-in-hand with an utter neglect of scientific method or knowledge,’ while August Derleth in 1962 similarly notes that ’The Vampire in Europe is a curious work, a volume of pseudo-scholarship written with a fascinating air of authority, offering between two covers a great deal of the lore Dr. Summers assembled from various sources.’

Reviewing the reprint in The Catholic Historical Review the following year, Ruth B. Dinbergs finds that: ’Much interesting material is included in this monograph, but it is presented in a dispersed and unsystematic way. The book seems written in haste. Legends and tales are related which show only the vaguest connection with vampirism as defined in this work. The book is divided into chapters according to countries, yet the author does not stay consistently within these confines. The numerous notes following each chapter testify to the broad erudition of the author, but it is frequently difficult to judge where notes begin and the text leaves off.’

A more in-depth review of Summers’s approach to the subject and his use and neglect of sources was undertaken by Gustave Leopold Van Roosbroeck of Columbia University in The Romanic Review in 1930. He mentions several sources that Summers has neglected, while at the same time he criticizes the sources that Summers does actually take into account, before stating that: ’This study seems to rest on a vague notion of the meaning of Vamprism. It is impossible to explain, for instance, the inclusion (with an illustration) of Huysmans’ Black Mass from À Rebours among vampire lore, when it is evidently a case of devil-worship; the illustrations from Goya’s Los Caæprichos deal with the Sabbath and witchcraft, and not with vampires; and it is strange to find a description of popular superstition from D’Annunzio’s Trionfo della Morte in this miscellaneous collection. With this lack of discrimination, the author could have included the entire history of witchcraft and half of folklore.’

Bringing it up to our day, Carol A. Senf in her afterword characterizes Summers's work along the same line as the just quoted reviewers:

’Summers moves casually from the ancient world to the medieval and from one part of the globe to another, cavalierly mising legends, literature, and folktales and treating even the most improbable cases with total seriousness. The experience is a bit like listening to a garrulous old uncle who interrupts himself and moves cavalierly from one story to the next, not stopping to take breaths between anecdotes.

His organization is equally eccentric. Even though his table of contents suggests that he is organizing his cases geographically, they are actually a hodge-podge of materials collected from literature, folklore, and personal anecdote.'

Adding that ’despite my criticism of his organization and his aesthetics, I was (and am) grateful for Summer’s research,’ she states exactly that ambivalence that many people have with regards to Summers: On the one hand, he is an unrealiable and inconsistent researcher, on the other he can be fascinating to read, and for a long time he was probably the main, if not sole, source for information on vampires and related subjects.

This ambivalence was nicely phrased by Marco Frenschkowski, as I mentioned in a post in 2013, that many of the scholars who denounce Summers’s books on witchcraft probably read his books discreetly.

So Summers has his particular, quaint fascination and charm, and Gerard P. O’Sullivan coins a phrase for it in a prologue to The Vampire in Europe: A Critical Edition: Summers-ism.

Claiming that The Vampire in Europe is a casebook modelled on the work of Summers's friend and intellectual mentor, the Edwardian sexologist Havelock Ellis, he firmly states that the roots of Summers's views on vampires and related subjects are not in orthodox Catholicism, but in ’a strange syncretism’:

’Those who praise or blame Summers for his putative ultra-orthodoxy are missing an essential point: Summers believed in Summers-ism, and even long after his covert ordination to the Catholic priesthood. Dig deeply enough into the footnotes of Summers’s studies and you will find Tertullian and St. Thomas Aquinas rubbing elbows with the sexologist Havelock Ellis, the German physician and occultist Franz Hartmann, practitioners of Victorian parlor mysticism, and trance mediums and spiritualists of all kinds. If reading Summers appears to stretch a reader’s credulity, it is because the writer himself believed so many contradictory notions simultaneously. He accepted as established fact many things which any skeptic, rationalist or even conventional Catholic would dismiss out of hand.’

Personally, I feel unsure to what extent Summers actually believed in the existence of vampires, or if his claims to do so were rather a gimmick, a way of setting himself up to sell his pseudo-baroque collections of witchcraft, vampire and werewolf stories? In any case, it should be obvious that one cannot expect Summers to be systematic, consistent or reliable, but rather the opposite, and even self-contradictory. Summers-ism makes for fascinating reading and a vast resource to dip into, but not a voice of scholarship in any traditional sense.

Recently, The Apocryphile Press has published The Vampire in Europe: A Critical Edition, once again edited by Browning, who in his preface remarks on the mission of these critical editions: ’Our approach, as literary critic Maurice Hindle noted after the fact, was instead a ”disinterested appraisal,” one aimed at re-visiting a familiar yet widely unexplored work with renewed perspective and interest in order that we may situate the book and its author in their historical context.’

I think that I have stated my mind on the matter in the aforementioned posts, but I am also happy to note that the new book does in fact include voices that comment on the style and contents of Summers’s work, because Browning has included excerpts from original reviews of The Vampire in Europe, both from 1929 when it was originally published and from 1960 onwards when it was reprinted.

Thus, according to a reviewer in The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer on November 27, 1929, Summers’s ’new book, like its predecessor, ”The Vampire: His Kith and Kin,” reveals an astonishing learning hand-in-hand with an utter neglect of scientific method or knowledge,’ while August Derleth in 1962 similarly notes that ’The Vampire in Europe is a curious work, a volume of pseudo-scholarship written with a fascinating air of authority, offering between two covers a great deal of the lore Dr. Summers assembled from various sources.’

Reviewing the reprint in The Catholic Historical Review the following year, Ruth B. Dinbergs finds that: ’Much interesting material is included in this monograph, but it is presented in a dispersed and unsystematic way. The book seems written in haste. Legends and tales are related which show only the vaguest connection with vampirism as defined in this work. The book is divided into chapters according to countries, yet the author does not stay consistently within these confines. The numerous notes following each chapter testify to the broad erudition of the author, but it is frequently difficult to judge where notes begin and the text leaves off.’

A more in-depth review of Summers’s approach to the subject and his use and neglect of sources was undertaken by Gustave Leopold Van Roosbroeck of Columbia University in The Romanic Review in 1930. He mentions several sources that Summers has neglected, while at the same time he criticizes the sources that Summers does actually take into account, before stating that: ’This study seems to rest on a vague notion of the meaning of Vamprism. It is impossible to explain, for instance, the inclusion (with an illustration) of Huysmans’ Black Mass from À Rebours among vampire lore, when it is evidently a case of devil-worship; the illustrations from Goya’s Los Caæprichos deal with the Sabbath and witchcraft, and not with vampires; and it is strange to find a description of popular superstition from D’Annunzio’s Trionfo della Morte in this miscellaneous collection. With this lack of discrimination, the author could have included the entire history of witchcraft and half of folklore.’

Bringing it up to our day, Carol A. Senf in her afterword characterizes Summers's work along the same line as the just quoted reviewers:

’Summers moves casually from the ancient world to the medieval and from one part of the globe to another, cavalierly mising legends, literature, and folktales and treating even the most improbable cases with total seriousness. The experience is a bit like listening to a garrulous old uncle who interrupts himself and moves cavalierly from one story to the next, not stopping to take breaths between anecdotes.

His organization is equally eccentric. Even though his table of contents suggests that he is organizing his cases geographically, they are actually a hodge-podge of materials collected from literature, folklore, and personal anecdote.'

Adding that ’despite my criticism of his organization and his aesthetics, I was (and am) grateful for Summer’s research,’ she states exactly that ambivalence that many people have with regards to Summers: On the one hand, he is an unrealiable and inconsistent researcher, on the other he can be fascinating to read, and for a long time he was probably the main, if not sole, source for information on vampires and related subjects.

This ambivalence was nicely phrased by Marco Frenschkowski, as I mentioned in a post in 2013, that many of the scholars who denounce Summers’s books on witchcraft probably read his books discreetly.

|

| Decadence and Catholicism (1997) by Ellis Hanson, p. 346 |

Claiming that The Vampire in Europe is a casebook modelled on the work of Summers's friend and intellectual mentor, the Edwardian sexologist Havelock Ellis, he firmly states that the roots of Summers's views on vampires and related subjects are not in orthodox Catholicism, but in ’a strange syncretism’:

’Those who praise or blame Summers for his putative ultra-orthodoxy are missing an essential point: Summers believed in Summers-ism, and even long after his covert ordination to the Catholic priesthood. Dig deeply enough into the footnotes of Summers’s studies and you will find Tertullian and St. Thomas Aquinas rubbing elbows with the sexologist Havelock Ellis, the German physician and occultist Franz Hartmann, practitioners of Victorian parlor mysticism, and trance mediums and spiritualists of all kinds. If reading Summers appears to stretch a reader’s credulity, it is because the writer himself believed so many contradictory notions simultaneously. He accepted as established fact many things which any skeptic, rationalist or even conventional Catholic would dismiss out of hand.’

Personally, I feel unsure to what extent Summers actually believed in the existence of vampires, or if his claims to do so were rather a gimmick, a way of setting himself up to sell his pseudo-baroque collections of witchcraft, vampire and werewolf stories? In any case, it should be obvious that one cannot expect Summers to be systematic, consistent or reliable, but rather the opposite, and even self-contradictory. Summers-ism makes for fascinating reading and a vast resource to dip into, but not a voice of scholarship in any traditional sense.

Friday, 24 October 2014

Britain's Midnight Hour

BBC joins the British Library in celebrating 250 years of gothic in the arts. For more information see this overview. I am personally particularly interested to see Andrew Graham-Dixon's take on The Art of Gothic, cf. the youtube video below. If you are interested in the subject, I highly recommend his series on The Art of Germany, which is available on DVD if you don't happen to catch a re-run on BBC World or elsewhere.

Tuesday, 14 October 2014

Habsburg maps of Kisolova and Frey Hermersdorf online

Thanks to an international co-operation between a number of archives, including the Austrian State Archives, historical maps of the Habsburg Empire are now available in both 2D and 3D as layers on top of current Google Earth maps. The maps are searchable, so you can seek out a number of places that are e.g. relevant to the history of vampires and posthumous magic, including those shown below: Kisolova, the site of the first 'vampire case' concerning a certain Peter Plogojowitz, and Frey Hermersdorf, the site of an instance of magia posthuma that was investigated by the court physicians Johannes Gasser and Christian Wabst, described and analyzed by Gerard van Swieten, before prompting Empress Maria Theresa's decree concerning magia posthuma and other superstitions.

Historical Maps of the Habsburg Empire is an excellent resource worth investigating.

Saturday, 4 October 2014

Styrian settings

|

| Styrian Schloss Hainfeld from German Wikipedia |

A new book published in connection with the current exhibition Carmilla, der Vampir und wir at the GrazMuseum in Styria, explores how Styria became the location of fictional vampire tales, as well as the general evolution of the vampire from the early Eighteenth Century to the mass media of our day.

Hans-Peter Weingand discusses some of the sources for Carmilla that must have inspired Sheridan Le Fanu in setting his vampire tale only about 50 km from Graz, while Elizabeth Miller explores the Stoker connection, as Count Dracula (or was that Count Wampyr?) originally was meant to live in Styria. Peter Mario Kreuter writes about the vampire investigations of the Eighteenth Century and vampire beliefs, while Clemens Ruthner lines out the development of the vampire theme. Most contributions are in German, but three are actually in English.

Overall, a nice read about Le Fanu, vampires and Styria, with notes and bibliography for further reading. Included is also a set of photos from the exhibition, serving as either a souvenir from the exhibition or a substitute for traveling to Graz.

The contents are:

Annette Rainer, Christina Töpfer, Martina Zerovnik: Grenzerfahrung, Vampirismus

Brian J. Showers: The Life and Literature of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

Hans-Peter Weingand: Den leisen Schritt Carmillas … Wie die Vampire in die Steiermark kamen

Elizabeth Miller: From Styria to Transylvania

Peter Mario Kreuter: Vampirglaube in Südosteuropa einst und jetzt

Clemens Ruthner: Untot mit Biss: Kurze Kultur- und Erfolgsgeschichte des Vampirismus in unseren Breiten

Theresia Heimerl: Unsterblich und (un)moralisch? Der Vampir als Repräsentationsfigur von Wert- und Normierungsdiskursen

Laurence A. Rickels: Integration of the Vampire

Sabine Planka: Der Vampir in der Kinder- und Jugendliteratur

Martina Zerovnik: Zwischen Vampir und Vamp: Auf der Suche nach der ”Neuen Frau” in Carmilla, Dracula, Twilight & Co

Auswahlbibliographie

Carmilla, der Vampir und Wir is published by Passagen Verlag in Vienna and is available from GrazMuseum, the publishers, and Amazon.

A collection of books exhibited at the GrazMuseum.

Sunday, 21 September 2014

Albania's Mountain Queen

'Whilst young ladies in the Victorian and Edwardian eras were expected to have many creative accomplishments, they were not expected to travel unaccompanied, and certainly not to the remote corners of Southeast Europe, then part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. But Edith Durham was no ordinary lady. In 1900, at the age of 37, Durham set sail for the Balkans for the first time. Her trip was intended as a means of recovering from a period of ill-health, and as a break from the stifling monotony of caring for her ailing mother. Her experiences on this trip were to change the course of her life, kindling a profound love for the region which saw her return frequently in the following decades. She became a confidante of the King of Montenegro, ran a hospital in Macedonia and, following the outbreak of the First Balkan War in 1912, became one of the world's first female war correspondents. Back in England, she was renowned as an expert on the region, writing the highly successful book High Albania and, along with other aficionados such as the MP Aubrey Herbert, becoming an advocate for the people of the Balkans in British political life and society.

King Zog of Albania once said that before Durham visited the Balkans, Albania was but a geographical expression. By the time she left, he added, her championship of his compatriots' desire for freedom had helped add a new state to the map. Durham was tremendously popular in the region itself, earning her the affectionate title 'Queen of the Mountains' and an enduring legacy which continues unabated until this day. Yet she has been all but forgotten in the country of her birth. Marcus Tanner here tells the fascinating story of Durham's relationship with the Balkans, painting a vivid portrait of a remarkable, and sometimes formidable, woman, who was several decades ahead of her time.'

Marcus Tanner's Albania's Mountain Queen was published earlier this year by I.B.Tauris.

Durham's High Albania, including her information on 'that dire being the Shtriga, the vampire woman that sucks the blood of children, and bewitches even grown folk, so that they shrivel and die', is easily found second hand.

King Zog of Albania once said that before Durham visited the Balkans, Albania was but a geographical expression. By the time she left, he added, her championship of his compatriots' desire for freedom had helped add a new state to the map. Durham was tremendously popular in the region itself, earning her the affectionate title 'Queen of the Mountains' and an enduring legacy which continues unabated until this day. Yet she has been all but forgotten in the country of her birth. Marcus Tanner here tells the fascinating story of Durham's relationship with the Balkans, painting a vivid portrait of a remarkable, and sometimes formidable, woman, who was several decades ahead of her time.'

Marcus Tanner's Albania's Mountain Queen was published earlier this year by I.B.Tauris.

Durham's High Albania, including her information on 'that dire being the Shtriga, the vampire woman that sucks the blood of children, and bewitches even grown folk, so that they shrivel and die', is easily found second hand.

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Revenant - from Italy

Since Emilio de' Rossignoli published his groundbreaking Io credo nei vampiri back in 1961, a number of books on revenants and vampires have been written in Italy, including Massimo Introvigne's La stirpe di Dracula (1997) and Tommaso Braccini's Prima di Dracula (2011). Recently, young Italian historian Simonluca Renda penned another book on the subject, Revenant: Il retorno dei vampiri, a slim volume (136 pages) published by Hermatena, that draws heavily on Introvigne and other writers.

Renda writes about 18th century vampires, the masticating dead, Greek vampires, the vampire tales recounted by William of Newburgh and Walter Map, related myths from antiquity, and - most notably, I suppose - archaeological finds that may (or may not) be related to beliefs in vampires and revenants. A brief appendix deals with the so-called Highgate Vampire, and a bibliography as well as a handful of maps are included.

As I do not really read Italian, I am, unfortunately, only able to get an idea of the contents based on names and references. Consequently, there may be finer points and details that are not apparent to me from scrutinizing the text based on my knowledge of the subject. No doubt this is a nice read for the Italian reader - considering, however, the brevity of the book, it looks to me as if, at best, it mainly summarizes information and views that are available elsewhere, in particular in the books that Renda himself refers to.

Revenant is available from the publisher at € 15.50 from the publisher.

Renda writes about 18th century vampires, the masticating dead, Greek vampires, the vampire tales recounted by William of Newburgh and Walter Map, related myths from antiquity, and - most notably, I suppose - archaeological finds that may (or may not) be related to beliefs in vampires and revenants. A brief appendix deals with the so-called Highgate Vampire, and a bibliography as well as a handful of maps are included.

As I do not really read Italian, I am, unfortunately, only able to get an idea of the contents based on names and references. Consequently, there may be finer points and details that are not apparent to me from scrutinizing the text based on my knowledge of the subject. No doubt this is a nice read for the Italian reader - considering, however, the brevity of the book, it looks to me as if, at best, it mainly summarizes information and views that are available elsewhere, in particular in the books that Renda himself refers to.

Revenant is available from the publisher at € 15.50 from the publisher.

Monday, 4 August 2014

A Horrible Incident, a Delightful Find

The 2013 Dracula exhibition in Milano, Dracula e il mito dei vampiri, recently moved East, opening in a new reincarnation at the National Museum of History in Taipei, Taiwan. As one can see in the videos above and below, the exhibition elaborates along the lines of the Milanese exhibition, while also including e.g. Asian vampire comics. Despite the macabre subject, the exhibition is promoted in a humorous and family friendly way, and I am sure that the very young visitors shown in the youtube videos were in for a treat.

What, however, is of particular interest here is a reproduction of what appears to be the cover of a pamphlet that the museum has posted on Facebook. The pamphlet is the very rare Entsetzliche Begebenheit, Welche sich in dem Dorff Kisolova / ohnweit Belgard in Ober-Ungarn / vor einigen Tagen zugetragen, a reprint of Provisor Frombald's report about the purported vampire Peter Plogojowitz in the Serbian village Kisiljevo, at the time referred to as Kisolova (note also the misspelling of Belgrade).

This pamphlet is so rare that Schroeder, Hamberger et al only knew the title, because Stefan Hock back in 1900 in his literatury study of the vampire, Die Vampyrsagen und ihre Verwertung in der deutschen Literatur, mentions it in a note, himself referring the reader to the Austria from 1843, i.e. Austria oder Österreischischer Universal-Kalender für das gemeine Jahr 1843, as his source. The Austria contains a transcript of the pamphlet, but here, finally, of all places, a reproduction of the cover turns up not only on Facebook, but also in the youtube video above!

Neither a place of printing nor a more exact date of publishing than the year appears on the cover.

For more on the pamphlet, see this post from 2013.

Sunday, 22 June 2014

The Gothic Imagination

2014 marks the 250th anniversary of Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, usually celebrated as the first Gothic novel. The British Library will be celebrating the anniversary with an exhibition that opens on October 3 this year: Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination will be the most comprehensive exhibition on the subject in the UK so far:

'Beginning with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, this wide-ranging exhibition explores our enduring fascination with the mysterious, the terrifying and the awe-inspiring. It also examines the long shadow the Gothic imagination has cast across film, art, music, fashion, culture and our daily lives.

Gothic literature began as a challenge to the rational certainties of the Enlightenment. By exploring the harsh romance of the medieval past with its castles and abbeys, its wild landscapes and fascination with the supernatural, Gothic writers placed imagination firmly at the heart of their work.

Through over 200 rare exhibits including manuscripts, paintings, film clips and posters, Terror and Wonder explores all aspects of the Gothic world. Iconic works, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the sinister fairy tales of Angela Carter and the modern horrors of Clive Barker highlight the ways in which contemporary fears have been addressed by successive generations of Gothic writers. Paintings, films and even a vampire-slaying kit add colour and drama to the story.

Terror and Wonder promises to be beautiful, dark, inspiring and haunting. Step into this world, if you dare.'

The British Library web site already contains a theme on the subject, including, of course, a page on Dracula and vampire literature (incidentally, they also have a page on Emily Gerard's The Land beyond the Forest). They have also made a youtube video on the Gothic in which Professor John Bowen discusses Gothic motifs while wandering around Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill House.

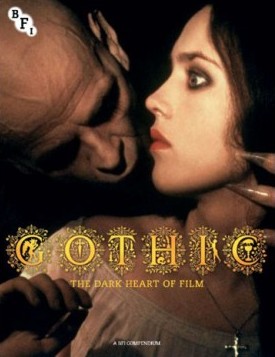

This exhibition follows hot on the heels of a Gothic film festival, Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film, arranged by the British Film Institute (BFI) in 2013. The BFI published a compendium, which is actually a delightful introduction to the world of Gothic film, its landscapes, architecture and inhabitants. In fact, this is probably one of the rare instances you will see me recommending a book on Gothic fiction on this blog, but the thematic approach to the subject as well as the host of experts who have contributed to it makes it a real treat, even for people with a more casual interest in the genre.

So the book includes essays on the relation between Gothic cinema and literature, architecture and art, with Martin Myrone, author of a nice book on Fuseli and contributor to the Tate exhibition on Gothic Nightmares back in 2006, noting that 'the relationship between the canon of Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase (c. 1760-1830) and the visual imagery of the same date is far from simple: the relationship of this early Gothic art and writing to modern cinema no more so.' Still, he later on concedes that 'nonetheless, there are parallels and resonances between Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase and precisely contemporary visual art, and between these and modern cinema,' accompanying his essay with a number of examples of these homologies, of which the most famous is, of course, Fuseli's Nightmare (see the Gothic Nightmares catalogue from Tate for numerous examples).

However many experts have contributed to the conpendium, they still are unable to solve the conundrum of pinning down what the Gothic 'genre' actually is. Myrone states that it is 'now often understood as, by definition, a trans-medial, genre-defying, migratory and polluting phenomenon, we should not expect homologies between Gothic productions in different media and eras need be predictable, explicit or orderly.' The paradox of how relatively easy it is to describe the Gothic 'landscape', while it seems almost impossible to define it, is what makes the compendium - cf. the title's nod to Joseph Conrad - a 'Grand Tour of the Gothic,' as Sir Christopher Frayling says in his foreword.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)