Many of these cases are documented - although often briefly - in contemporary sources, and the dead bodies not always appear as revenants, but are at times suspected of posthumous magic simply because they lack the expected signs of corruption. In other cases, they do actually disturb people, although not necessarily in the shape of the dead person, and usually they are not recorded to suck blood! In fact, one researcher rather considers these revenants as poltergeists than as vampires, whereas others relate them to other kinds of revenants known by other characteristics than blood sucking.

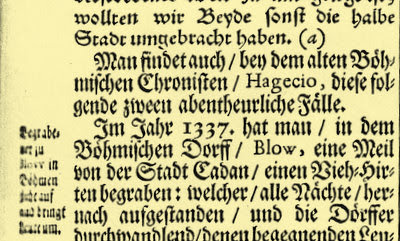

Von Schertz probably didn't know the word 'vampire', which first became well-known throughout Europe after the 1732 Medvedja vampire case, but he was aware of earlier tales of revenants. One tale was that of the shepherd from Blov in Bohemia (situated northwest of Prague at approximately latitude 56.324 N and longitude 13.295 E), which was also related by Johann Weichard Valvasor (1641-1693) in Die Ehre des Herzogthums Krain (1689). The story can be traced to the 16th century Böhmische Chronica written by Wenceslaus Hagecius (Wenzel Hajek von Libotschan/Václav Hájek z Libočan; died 1553) and further back to the Kronika Neplachova, i.e. Neplach's Chronicle, which is also known by the Latin title Summula Chronicae tam Romanae quam Bohemicae written by the Benedictine abbot Jan Neplach (1322-1371).

In the chronicle, the year 1336 A.D. is described this way:

"A. d. MCCCXXXVI Philippus, filius regis Maiorikarum, cum XII nobilibus regni ordinem fratrum Minorum in vigilia Nativitatis Christi ingreditur et in Boemia circa Cadanum ad milliare unum in villa dicta Blow quidam pastor nomine Myslata moritur. Hic omni nocte surgens circuibat omnes villas in circuitu hominus terrendo et iugulando et loquebatur. Et cum fuisset cum palo transfixus: dicebat, multum nocuerunt michi, nam dederunt michi baculum, ut me a canibus defendam ; et cum cremandus efoderetur, tumebat sicut bos et terribiliter rugiebat. Et cum poneretur in ignem, quidam arripiens fustem fixit in eum et continuo eupit cruor sicut de vase. Insuper cum fuisset effossus et in currum positus, collegit pedes ad se sicut vivus, et cum fuisset crematus totum malum conquievit, et antequam cremaretur, quemcumque ex nomine in nocte vocabat, infra octo dies moriebatur. Eodem eciam anno Johannes papa XXI moritur et Benedictus XII in papam eligitur.'

In my rudimentary translation this means:

''A.D. 1336 Philip, son of the king of Majorca, entered the [Franciscan] Order of Friars Minor along with 12 nobles of the kingdom on Christmas Eve Day. In Bohemia about one mile from Cadan in a village called Blow a certain shepherd called Myslata died. Every night he rose and went about every farm in the area and spoke to frighten and kill people. When he had been impaled with a stake, he said: They hurt me much, as they gave me a staff to defend me from the dogs; and when he was exhumed for cremation, he swelled up like an ox and roared terribly. When he was placed in the fire, someone grabbed a stick and put it into him, and immediately blood poured out from him as from a vessel. Furthermore, when he had been dug up and was being put on a cart, he drew his feet to himself as if alive, and before he was cremated, anyone whom he called by name at night, died within eight days. Also the same year the pope John XXI died and Benedict XII was elected as pope."

It is quite obvious that there is no mention of bloodsucking, and that blood ('cruor') is only mentioned in connection with the state of the dead body. His malice seems to be confined to haunting the neighbourhood and naming people who consequently die within eight days. The means that are used to destroy him are very similar to those used against vampires - stakes and fire - so, obviously, there are similarities, but would we call the shepherd a vampire or just a revenant?

Claude Lecouteux mentions the shepherd from Blov under the classification 'Rufer' (someone who yells or calls out) in the German translation of his book on vampires, as the deaths of his victims are caused by him saying aloud their names (and thereby probably calling them to him).

So it would be more appropriate to use the term Magia Posthuma in this case, as this term seems to cover both vampires and other revenants that haunt and molest the living, whose corpses exhibit no signs of ordinary corruption and must be destroyed by various means to stop the threat from the dead. I admit that I know of no use of the term prior to Von Schertz's book, but I find the term fitting for a subject that cannot be restricted to the Serbian vampire of the 18th century, but must take into account prior cases of 'living corpses' from other parts of Europe.

Finally, I like the term because it includes the word Magia and consequently can be linked to both the witch hunt and various 'systems of belief' that involved the concept of 'Magia', which incidentally is usually translated as 'Zauberei' in German. 'Magia Posthuma' thereby presents us with a link to the history and concepts of theology, demonology and witchcraft cases that can help us better understand the context of the famous cases of vampires and revenants of the 17th and 18th centuries. In fact, certain scholars claim that in some areas the witch hunt was succeeded by the cases of vampires and other forms of Magia Posthuma.

By the way, according to The Oxford Dictionary of Popes, pope John XII died on December 4th 1334 and was succeeded by Benedict XII on December 20th that year, so obviously Neplach's dates are not precise! As the above excerpt from Valvasor's book shows, he sets the incident in 1337, so here is a good example of how a story has evolved over the years.

The Latin text of Neplach's chronicle is actually available on the internet.

No comments:

Post a Comment