BBC joins the British Library in celebrating 250 years of gothic in the arts. For more information see this overview. I am personally particularly interested to see Andrew Graham-Dixon's take on The Art of Gothic, cf. the youtube video below. If you are interested in the subject, I highly recommend his series on The Art of Germany, which is available on DVD if you don't happen to catch a re-run on BBC World or elsewhere.

On several occasions, particularly on the periphery of the Habsburg Empire during the 17th and 18th centuries, dead people were suspected of being revenants or vampires, and consequently dug up and destroyed. Some contemporary authors named this phenomenon Magia Posthuma. This blog is dedicated to understanding what happened and why.

Friday, 24 October 2014

Britain's Midnight Hour

BBC joins the British Library in celebrating 250 years of gothic in the arts. For more information see this overview. I am personally particularly interested to see Andrew Graham-Dixon's take on The Art of Gothic, cf. the youtube video below. If you are interested in the subject, I highly recommend his series on The Art of Germany, which is available on DVD if you don't happen to catch a re-run on BBC World or elsewhere.

Tuesday, 14 October 2014

Habsburg maps of Kisolova and Frey Hermersdorf online

Thanks to an international co-operation between a number of archives, including the Austrian State Archives, historical maps of the Habsburg Empire are now available in both 2D and 3D as layers on top of current Google Earth maps. The maps are searchable, so you can seek out a number of places that are e.g. relevant to the history of vampires and posthumous magic, including those shown below: Kisolova, the site of the first 'vampire case' concerning a certain Peter Plogojowitz, and Frey Hermersdorf, the site of an instance of magia posthuma that was investigated by the court physicians Johannes Gasser and Christian Wabst, described and analyzed by Gerard van Swieten, before prompting Empress Maria Theresa's decree concerning magia posthuma and other superstitions.

Historical Maps of the Habsburg Empire is an excellent resource worth investigating.

Saturday, 4 October 2014

Styrian settings

|

| Styrian Schloss Hainfeld from German Wikipedia |

A new book published in connection with the current exhibition Carmilla, der Vampir und wir at the GrazMuseum in Styria, explores how Styria became the location of fictional vampire tales, as well as the general evolution of the vampire from the early Eighteenth Century to the mass media of our day.

Hans-Peter Weingand discusses some of the sources for Carmilla that must have inspired Sheridan Le Fanu in setting his vampire tale only about 50 km from Graz, while Elizabeth Miller explores the Stoker connection, as Count Dracula (or was that Count Wampyr?) originally was meant to live in Styria. Peter Mario Kreuter writes about the vampire investigations of the Eighteenth Century and vampire beliefs, while Clemens Ruthner lines out the development of the vampire theme. Most contributions are in German, but three are actually in English.

Overall, a nice read about Le Fanu, vampires and Styria, with notes and bibliography for further reading. Included is also a set of photos from the exhibition, serving as either a souvenir from the exhibition or a substitute for traveling to Graz.

The contents are:

Annette Rainer, Christina Töpfer, Martina Zerovnik: Grenzerfahrung, Vampirismus

Brian J. Showers: The Life and Literature of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

Hans-Peter Weingand: Den leisen Schritt Carmillas … Wie die Vampire in die Steiermark kamen

Elizabeth Miller: From Styria to Transylvania

Peter Mario Kreuter: Vampirglaube in Südosteuropa einst und jetzt

Clemens Ruthner: Untot mit Biss: Kurze Kultur- und Erfolgsgeschichte des Vampirismus in unseren Breiten

Theresia Heimerl: Unsterblich und (un)moralisch? Der Vampir als Repräsentationsfigur von Wert- und Normierungsdiskursen

Laurence A. Rickels: Integration of the Vampire

Sabine Planka: Der Vampir in der Kinder- und Jugendliteratur

Martina Zerovnik: Zwischen Vampir und Vamp: Auf der Suche nach der ”Neuen Frau” in Carmilla, Dracula, Twilight & Co

Auswahlbibliographie

Carmilla, der Vampir und Wir is published by Passagen Verlag in Vienna and is available from GrazMuseum, the publishers, and Amazon.

A collection of books exhibited at the GrazMuseum.

Sunday, 21 September 2014

Albania's Mountain Queen

'Whilst young ladies in the Victorian and Edwardian eras were expected to have many creative accomplishments, they were not expected to travel unaccompanied, and certainly not to the remote corners of Southeast Europe, then part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. But Edith Durham was no ordinary lady. In 1900, at the age of 37, Durham set sail for the Balkans for the first time. Her trip was intended as a means of recovering from a period of ill-health, and as a break from the stifling monotony of caring for her ailing mother. Her experiences on this trip were to change the course of her life, kindling a profound love for the region which saw her return frequently in the following decades. She became a confidante of the King of Montenegro, ran a hospital in Macedonia and, following the outbreak of the First Balkan War in 1912, became one of the world's first female war correspondents. Back in England, she was renowned as an expert on the region, writing the highly successful book High Albania and, along with other aficionados such as the MP Aubrey Herbert, becoming an advocate for the people of the Balkans in British political life and society.

King Zog of Albania once said that before Durham visited the Balkans, Albania was but a geographical expression. By the time she left, he added, her championship of his compatriots' desire for freedom had helped add a new state to the map. Durham was tremendously popular in the region itself, earning her the affectionate title 'Queen of the Mountains' and an enduring legacy which continues unabated until this day. Yet she has been all but forgotten in the country of her birth. Marcus Tanner here tells the fascinating story of Durham's relationship with the Balkans, painting a vivid portrait of a remarkable, and sometimes formidable, woman, who was several decades ahead of her time.'

Marcus Tanner's Albania's Mountain Queen was published earlier this year by I.B.Tauris.

Durham's High Albania, including her information on 'that dire being the Shtriga, the vampire woman that sucks the blood of children, and bewitches even grown folk, so that they shrivel and die', is easily found second hand.

King Zog of Albania once said that before Durham visited the Balkans, Albania was but a geographical expression. By the time she left, he added, her championship of his compatriots' desire for freedom had helped add a new state to the map. Durham was tremendously popular in the region itself, earning her the affectionate title 'Queen of the Mountains' and an enduring legacy which continues unabated until this day. Yet she has been all but forgotten in the country of her birth. Marcus Tanner here tells the fascinating story of Durham's relationship with the Balkans, painting a vivid portrait of a remarkable, and sometimes formidable, woman, who was several decades ahead of her time.'

Marcus Tanner's Albania's Mountain Queen was published earlier this year by I.B.Tauris.

Durham's High Albania, including her information on 'that dire being the Shtriga, the vampire woman that sucks the blood of children, and bewitches even grown folk, so that they shrivel and die', is easily found second hand.

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Revenant - from Italy

Since Emilio de' Rossignoli published his groundbreaking Io credo nei vampiri back in 1961, a number of books on revenants and vampires have been written in Italy, including Massimo Introvigne's La stirpe di Dracula (1997) and Tommaso Braccini's Prima di Dracula (2011). Recently, young Italian historian Simonluca Renda penned another book on the subject, Revenant: Il retorno dei vampiri, a slim volume (136 pages) published by Hermatena, that draws heavily on Introvigne and other writers.

Renda writes about 18th century vampires, the masticating dead, Greek vampires, the vampire tales recounted by William of Newburgh and Walter Map, related myths from antiquity, and - most notably, I suppose - archaeological finds that may (or may not) be related to beliefs in vampires and revenants. A brief appendix deals with the so-called Highgate Vampire, and a bibliography as well as a handful of maps are included.

As I do not really read Italian, I am, unfortunately, only able to get an idea of the contents based on names and references. Consequently, there may be finer points and details that are not apparent to me from scrutinizing the text based on my knowledge of the subject. No doubt this is a nice read for the Italian reader - considering, however, the brevity of the book, it looks to me as if, at best, it mainly summarizes information and views that are available elsewhere, in particular in the books that Renda himself refers to.

Revenant is available from the publisher at € 15.50 from the publisher.

Renda writes about 18th century vampires, the masticating dead, Greek vampires, the vampire tales recounted by William of Newburgh and Walter Map, related myths from antiquity, and - most notably, I suppose - archaeological finds that may (or may not) be related to beliefs in vampires and revenants. A brief appendix deals with the so-called Highgate Vampire, and a bibliography as well as a handful of maps are included.

As I do not really read Italian, I am, unfortunately, only able to get an idea of the contents based on names and references. Consequently, there may be finer points and details that are not apparent to me from scrutinizing the text based on my knowledge of the subject. No doubt this is a nice read for the Italian reader - considering, however, the brevity of the book, it looks to me as if, at best, it mainly summarizes information and views that are available elsewhere, in particular in the books that Renda himself refers to.

Revenant is available from the publisher at € 15.50 from the publisher.

Monday, 4 August 2014

A Horrible Incident, a Delightful Find

The 2013 Dracula exhibition in Milano, Dracula e il mito dei vampiri, recently moved East, opening in a new reincarnation at the National Museum of History in Taipei, Taiwan. As one can see in the videos above and below, the exhibition elaborates along the lines of the Milanese exhibition, while also including e.g. Asian vampire comics. Despite the macabre subject, the exhibition is promoted in a humorous and family friendly way, and I am sure that the very young visitors shown in the youtube videos were in for a treat.

What, however, is of particular interest here is a reproduction of what appears to be the cover of a pamphlet that the museum has posted on Facebook. The pamphlet is the very rare Entsetzliche Begebenheit, Welche sich in dem Dorff Kisolova / ohnweit Belgard in Ober-Ungarn / vor einigen Tagen zugetragen, a reprint of Provisor Frombald's report about the purported vampire Peter Plogojowitz in the Serbian village Kisiljevo, at the time referred to as Kisolova (note also the misspelling of Belgrade).

This pamphlet is so rare that Schroeder, Hamberger et al only knew the title, because Stefan Hock back in 1900 in his literatury study of the vampire, Die Vampyrsagen und ihre Verwertung in der deutschen Literatur, mentions it in a note, himself referring the reader to the Austria from 1843, i.e. Austria oder Österreischischer Universal-Kalender für das gemeine Jahr 1843, as his source. The Austria contains a transcript of the pamphlet, but here, finally, of all places, a reproduction of the cover turns up not only on Facebook, but also in the youtube video above!

Neither a place of printing nor a more exact date of publishing than the year appears on the cover.

For more on the pamphlet, see this post from 2013.

Sunday, 22 June 2014

The Gothic Imagination

2014 marks the 250th anniversary of Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, usually celebrated as the first Gothic novel. The British Library will be celebrating the anniversary with an exhibition that opens on October 3 this year: Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination will be the most comprehensive exhibition on the subject in the UK so far:

'Beginning with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, this wide-ranging exhibition explores our enduring fascination with the mysterious, the terrifying and the awe-inspiring. It also examines the long shadow the Gothic imagination has cast across film, art, music, fashion, culture and our daily lives.

Gothic literature began as a challenge to the rational certainties of the Enlightenment. By exploring the harsh romance of the medieval past with its castles and abbeys, its wild landscapes and fascination with the supernatural, Gothic writers placed imagination firmly at the heart of their work.

Through over 200 rare exhibits including manuscripts, paintings, film clips and posters, Terror and Wonder explores all aspects of the Gothic world. Iconic works, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the sinister fairy tales of Angela Carter and the modern horrors of Clive Barker highlight the ways in which contemporary fears have been addressed by successive generations of Gothic writers. Paintings, films and even a vampire-slaying kit add colour and drama to the story.

Terror and Wonder promises to be beautiful, dark, inspiring and haunting. Step into this world, if you dare.'

The British Library web site already contains a theme on the subject, including, of course, a page on Dracula and vampire literature (incidentally, they also have a page on Emily Gerard's The Land beyond the Forest). They have also made a youtube video on the Gothic in which Professor John Bowen discusses Gothic motifs while wandering around Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill House.

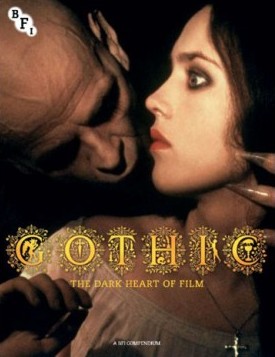

This exhibition follows hot on the heels of a Gothic film festival, Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film, arranged by the British Film Institute (BFI) in 2013. The BFI published a compendium, which is actually a delightful introduction to the world of Gothic film, its landscapes, architecture and inhabitants. In fact, this is probably one of the rare instances you will see me recommending a book on Gothic fiction on this blog, but the thematic approach to the subject as well as the host of experts who have contributed to it makes it a real treat, even for people with a more casual interest in the genre.

So the book includes essays on the relation between Gothic cinema and literature, architecture and art, with Martin Myrone, author of a nice book on Fuseli and contributor to the Tate exhibition on Gothic Nightmares back in 2006, noting that 'the relationship between the canon of Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase (c. 1760-1830) and the visual imagery of the same date is far from simple: the relationship of this early Gothic art and writing to modern cinema no more so.' Still, he later on concedes that 'nonetheless, there are parallels and resonances between Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase and precisely contemporary visual art, and between these and modern cinema,' accompanying his essay with a number of examples of these homologies, of which the most famous is, of course, Fuseli's Nightmare (see the Gothic Nightmares catalogue from Tate for numerous examples).

However many experts have contributed to the conpendium, they still are unable to solve the conundrum of pinning down what the Gothic 'genre' actually is. Myrone states that it is 'now often understood as, by definition, a trans-medial, genre-defying, migratory and polluting phenomenon, we should not expect homologies between Gothic productions in different media and eras need be predictable, explicit or orderly.' The paradox of how relatively easy it is to describe the Gothic 'landscape', while it seems almost impossible to define it, is what makes the compendium - cf. the title's nod to Joseph Conrad - a 'Grand Tour of the Gothic,' as Sir Christopher Frayling says in his foreword.

Sunday, 8 June 2014

Vampyrismus & Magia posthuma

By chance, years ago I watched part of a programme on History Channel about vampires in which anthropologist Giuseppe Maiello from the Charles University, Univerzita Karlova, in Prague was interviewed about vampires. I recall contacting Maiello who responded that he had himself not seen that interview. At the same time I learned about the book he had written on vampires, Vampyrismus v kulturních dĕjinách Evropy, which had been published in 2004, and got hold of it to see what a Czech researcher would include in a book on this subject.

Now Maiello has published a new edition of the book, this time titled Vampyrismus & Magia posthuma, and the new title indicates the major addition that has been made in this edition: A Czech translation of Karl Ferdinand von Schertz’s Magia Posthuma has been added to the sources at the end of the book!

The new edition also includes a foreword mentioning some of the work that has been published since the first edition, as well as summaries in English, French and Italian that can be helpful to those of us who are not proficient in the Czech language. Furthermore, a number of illustrations have been added, in particular of some key persons, including one of Schertz, which is unfortunately not of the best quality.

According to the English summary, 'Vampyrismus a Magia posthuma [Vampirism and Magia posthuma] is an updated version of Vampyrismus v kulturních dějinách Evropy [Vampirism in the cultural history of Europe], which had first appeared in bookstores back in 2005. The book describes the phenomenon of Vampirism from an etymological, cultural-historical, ethnographic and anthropological point of view.

Up until now, the sources of the book were found primarily in the libraries of the Czech Republic. For this reason the book includes both classic examples from the literature of Western countries, transmitted through the intermediation of Abbot Augustine Calmet, as well as examples taken from the ethnographic literature of Central and Eastern European countries and the Balkans; lesser known or completely unknown to wider audiences and to western European and northern American specialists.

The second part of the book deals with the main theories on the origins of vampirism through the comparison between different cultures, and across temporal space, from classical antiquity up to the late nineteenth century. These theories concentrate on three areas: universal theories of the origins and prehistory of vampirism; theories (less probable) that derive vampirism by social and cultural changes that took place in modern Europe; and theories related to the analysis of agrarian cults and their struggles for the fertility of the fields.

In addition to other texts already published or translated into other languages, this is the first time that there is published in a modern language the Karl Ferdinand Schertz's study Magia posthuma, which had been released only once in a printed Latin edition in 1704 (but which had the date 1706 written on the title page).'

Maiello has also published a paper on Schertz in 2012 in Slavica litteraria, Racionalismus Karla Ferdinada Schertze a Magia posthuma (Karl Ferdinand Schertz's rationalism and Magia posthuma). Written in Czech, it does however include an English abstract:

'Karl Ferdinand Schertz is at home a no well known author. On the contrary, his name is known around the world thanks to his work Magia posthuma, which was quoted by Augustin Calmet. Because of his not well available biography and books, Schertz is unfortunately wrong understood and around him circulate various rumors or negative critics. Karl Ferdinand Schertz was on the contrary highly cultured author, who could enjoy a good reputation among the european intellectuals of his time.'

The paper briefly deals with Schertz's life and works, and discusses his approach to magia posthuma, which in Maiello's view make Schertz more of a rationalist than a man of the Baroque period. Maiello actually finds that the rationalistic approach of Schertz is comparable to that of Calmet. Cf. what I have myself written in Vampirismus und magia posthuma im Diskurs der Habsburgermonarchie edited by Augustynowiz and Reber (or as part of Kakanien Revisited).

Giuseppe Maiello talks about vampires on this Czech talk show

I thank Giuseppe Maiello for providing me with a copy of his book. He informs me that the publisheres are considering publishing an edition in English.

Saturday, 17 May 2014

'There we saw many corpses impaled, many old, many fresh.'

Whether I first learned of Vlad the Impaler from reading some newspaper article or from watching the Swedish TV documentary Vem var Dracula? (Who was Dracula?, internationally known as In Search of Dracula), I am not sure. In any case, from a very young age I was aware of the supposedly 'historical origins' of Count Dracula, the vampire. Of course, McNally and Florescu did not come up with this idea when they published their bestselling In Search of Dracula, as one e.g. finds a reference to 'Voivode Drakula or Dracula, who ruled in Walachia in 1455-1462' in Harry Ludlam's Stoker biography from 1962, but it was their book that internationally established 'historical Dracula', Vlad Tepes, as a 'historical fact'.

|

| The Romanian stamp indicates the size of the book. |

Dieter Harmening's Der Anfang von Dracula. Zur Geschichte von Geschichte, published a decade later, on the other hand encourages the reader to follow in the footsteps of the historian reading source texts on the Impaler, as well as looking for the link between Vlad the Impaler and Count Dracula, the vampire.

This approach can now be carried out in full from your desk with the publication of the first of a three volume set Corpus Draculianum edited by Thomas M. Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe and Albert Weber, that collects all major sources for the life and deeds of Vlad the Impaler. The first volume is actually number 3, which collects sources from Ottoman world, written by both Muslim and Post-Byzantine Christian authors and as a whole complementing the more well-known European view of the Impaler with an Oriental Dracula figure.

The texts are mainly first and second hand sources, with only a few of the most important tertiary sources added. The primary sources were written by people who had been involved in Sultan Mehmed II's campaign against Vlad Tepes in 1462. Among them, Enveri has himself apparently seen many impaled corpses in Wallachia: 'Als jener abgezogen war, sahen wir dort viele Leichen/Auf den Pfähl [gezogen], manche alt, manche neu.'

The focus of most texts is the campaign, and some of the authors seem to have little knowledge of what happend to the Impaler after his escape to Hungary. Tursun Beg, one of the more well-known Ottoman authors, even believed that Vlad Tepes died in captivity in Hungary, his soul ending up in Hell: 'Die Ungarn nahmen ihn fest und kerkerten ihn ein. Und hier schickte er seine Seele in die Hölle.'

The Ottoman Dracula figure retains its own character until the 17th century, when it gradually takes on the shape of the Vlad the Impaler from the European tradition, that is reflected in e.g. the stories recounted by McNally and Florescu in their In Search of Dracula.

Each text in the Corpus is presented in the original language along with a German translation. Extensive notes are supplied to make the text easier to understand and appreciate, just as information on the authors, their motivations, the sources themselves and secondary literature accompany each text. Furthermore, a chronology of events and an index of names and places are included along with a minute analysis of the interrelation between the texts.

Although, no doubt only a specialist can genuinely appreciate and critically evaluate a work of this kind, I am confident that this volume provides invaluable information for the specialist and historian interested in Vlad the Impaler or in the history of the region during this period. The layman interested in uncovering the bare bones behind the recreation of historical events that have become associated with a popular figure of modern cultural history, will no doubt find it intriguing to witness 'history in the making'.

The other two volumes will folow within the next ear or two, and I am also told that Bohn, Gheorge, and Weber hope to present the Corpus in English later on.

In connection with the publication of the Corpus Draculianum, Professor Bohn is organizing a conference about Vlad Dracula later this year: Vlad Dracula - Tyrann oder Volkstribun? Historische Reizfiguren im Donau-Balkan-Raum:

'Vlad III. Ţepeş „Dracula“ ist durch eine Reihe von Gräueltaten im historischen Gedächtnis verankert. Das aus einer zeitgenössischen Rufmordkampagne resultierende Image rekurrierte vor allem auf seine vermeintliche despotische Blutrünstigkeit. Im Pantheon des rumänischen Geschichtsdenkens erwarb er sich hingegen einen Heldenplatz, da er die Auseinandersetzung mit Mehmed II., dem Eroberer Konstantinopels, gesucht hatte. Osmanische Chroniken schildern Vlad aber als ungläubigen und tyrannischen Rebellen, der unschädlich gemacht werden musste, um eine Pax Ottomana im europäischen Südosten herbeiführen und legitimieren zu können. Zwischen den Zeilen kristallisiert sich aus den Quellen jedoch auch das Bild eines Kreuzritters oder Volkstribunen heraus. Dass Vlad letztlich von Ungarn, Sachsen und Bojaren verraten wurde, machte deren moralische Argumentationsstrategien obsolet und erleichterte es der späteren rumänischen Nationalhistoriographie, ihren Heroen zu idealisieren. Bis heute verfügt die Forschung über keine nach zeitgemäßen wissenschaftlichen Kriterien verfasste Biographie des Vlad Ţepeş oder eine eingehende Aufarbeitung der späteren Erinnerungskulturen und historiographischen Debatten über ihn.

Gerade die Vita des Vlad Ţepeş bietet sich an, um über verschiedenartige kulturelle Prägungen charismatischer Herrscherpersönlichkeiten in Südosteuropa während des Spätmittelalters und in der frühen Neuzeit nachzudenken. Die Tagung soll deshalb in einer Vergleichsperspektive die komplexen Lebensläufe auch anderer Herrscher sowie die damals und heute damit verknüpften Erinnerungskulturen in den Blick nehmen. Übergreifend sollen Einblicke in eine große Zone der geschichtlichen Verflechtungen zwischen Ostmitteleuropa und dem Osmanischen Reich ermöglicht werden.

Anlass der Tagung ist die dreibändige Dokumentation „Corpus Draculianum“, deren erster Teil in Kürze von Thomas Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe und Albert Weber bei Harassowitz in Wiesbaden veröffentlicht wird.

Konferenzsprachen sind deutsch und englisch. Die Manuskripte der Vorträge sollen den Organisatoren zu Beginn der Tagung vorliegen und werden später in einem Sammelband publiziert.'

Corpus Dralianum 3. Die Überlieferung aus dem Osmanischen Reich costs € 68, and can be purchased directly from the publishers, Harassowitz Verlag.

|

| Ottoman booty from the 16th century collected at Castle Ambras, Innsbruck |

Wednesday, 23 April 2014

Sold ...

So what are the old books from the vampire debate of 1732 worth these days? It is probably fair to say that they - unlike copies of Calmet's work - are very scarce, so it would take some time to find just one for sale. On the internet you can see that a volume containing two of these books was sold in 2011 for almost four thousand Euro, more than ten times the estimate of 350 Euros. So not only are these books scarce, people (or, hopefully, libraries or other institutions) are willing to pay a lot for them!

Then in this instance, one of them, the anonymous Visum & Repertum published in Nürnberg in 1732 is no doubt one of the rarer books of this kind, so that may account for the result.

Fortunately, both books are available online, cf. my list on the right-hand side of the blog.

'Lot: 51

Fritsche, J. C.

[Fritsche, Joh. Chr.], Eines Weimarischen Medici Muthmaßliche Gedancken von denen Vampyren, oder sogenannten Blut-Saugern. Leipzig, M. Blochberger 1732. Pgt. d. Zt. mit hs. RTitel. 8vo. 80 S.

Angeb.: [Anon.], Visum & Repertum. Über die so genannten Vampirs, oder Blut-Aussauger, so zu Medvegia in Servien, an der Türckischen Granitz, den 7. Januarii 1732 geschehen. Nebst einem Anhang, von dem Kauen und Schmatzen der Todten in Gräbern. Nürnberg, J. A. Schmidt 1732. 45 S. - Sturm/Völker S. 596. - Nicht bei Graesse, Magica sowie Rosenthal, Ackermann etc. - Erste Ausgabe, sehr rar. - Das erste zeitgenössische Druckwerk, das den Bericht über die Vampire im serbischen Medvyga einem größeren Publikum zugänglich machte. Das in Nürnberg erschienene Werk enthält zunächst das sogenannte Flückinger-Gutachten , benannt nach dem 'Regiments-Feldscherer' Johann Flückinger, der zusammen mit den Offizieren und Militärärzten Sigel, Baumgarten, Büttener und von Lindenfels einen Bericht über die Vorkommnisse in Medvyga verfaßte. Es folgt ein Bericht über das Auftauchen des Vampirs Peter Plogojovitz im Dorf Kisolova, datiert vom 6. April 1725, sowie eine Art Nachwort des bis heute anonym gebliebenen Herausgebers über das 'Kauen und Schmatzen der Toten'. - Gebräunt und tlw. leicht stockfleckig. - Zwei ausgesprochen seltene Hauptschriften der Leipziger Vampirismusdebatte zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts.

First edition, rare. - Last 6 pages with 'Gutachten der Königl. Preußischen Societät derer Wissenschafften, von denen Vampyren, oder Blut-Aussaugern', dated 11 March 1732. Contemp. vellum with lettering. 8vo. 80 pp. - Another manuscript by an anonymous author on the same topic bound in. First edition, very rare. - Browned and slightlöy foxed in places. - Two extremely rare works on the Leipzig Vampirism debate from the early 18th century.

Fritsche, J. C.

Von denen Vampyren. 1732

Result (incl. 20% surcharge): 3,960 EUR / 5,385 $

Estimate: 350 EUR / 476 $'

Then in this instance, one of them, the anonymous Visum & Repertum published in Nürnberg in 1732 is no doubt one of the rarer books of this kind, so that may account for the result.

Fortunately, both books are available online, cf. my list on the right-hand side of the blog.

'Lot: 51

Fritsche, J. C.

[Fritsche, Joh. Chr.], Eines Weimarischen Medici Muthmaßliche Gedancken von denen Vampyren, oder sogenannten Blut-Saugern. Leipzig, M. Blochberger 1732. Pgt. d. Zt. mit hs. RTitel. 8vo. 80 S.

Angeb.: [Anon.], Visum & Repertum. Über die so genannten Vampirs, oder Blut-Aussauger, so zu Medvegia in Servien, an der Türckischen Granitz, den 7. Januarii 1732 geschehen. Nebst einem Anhang, von dem Kauen und Schmatzen der Todten in Gräbern. Nürnberg, J. A. Schmidt 1732. 45 S. - Sturm/Völker S. 596. - Nicht bei Graesse, Magica sowie Rosenthal, Ackermann etc. - Erste Ausgabe, sehr rar. - Das erste zeitgenössische Druckwerk, das den Bericht über die Vampire im serbischen Medvyga einem größeren Publikum zugänglich machte. Das in Nürnberg erschienene Werk enthält zunächst das sogenannte Flückinger-Gutachten , benannt nach dem 'Regiments-Feldscherer' Johann Flückinger, der zusammen mit den Offizieren und Militärärzten Sigel, Baumgarten, Büttener und von Lindenfels einen Bericht über die Vorkommnisse in Medvyga verfaßte. Es folgt ein Bericht über das Auftauchen des Vampirs Peter Plogojovitz im Dorf Kisolova, datiert vom 6. April 1725, sowie eine Art Nachwort des bis heute anonym gebliebenen Herausgebers über das 'Kauen und Schmatzen der Toten'. - Gebräunt und tlw. leicht stockfleckig. - Zwei ausgesprochen seltene Hauptschriften der Leipziger Vampirismusdebatte zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts.

First edition, rare. - Last 6 pages with 'Gutachten der Königl. Preußischen Societät derer Wissenschafften, von denen Vampyren, oder Blut-Aussaugern', dated 11 March 1732. Contemp. vellum with lettering. 8vo. 80 pp. - Another manuscript by an anonymous author on the same topic bound in. First edition, very rare. - Browned and slightlöy foxed in places. - Two extremely rare works on the Leipzig Vampirism debate from the early 18th century.

Fritsche, J. C.

Von denen Vampyren. 1732

Result (incl. 20% surcharge): 3,960 EUR / 5,385 $

Estimate: 350 EUR / 476 $'

Monday, 21 April 2014

In search of Georg Tallar and other borderland vampire investigators

'While the belief in returning dead and the ritual/social practices related to it had already had a many-centuries-old, established tradition, it was the special relations of the borderland region [in the Southern parts of the Habsburg empire] which made them visible and problematized them for different officials of the state administration. At the same time, these same relations posed considerable difficulties for these functionaries to fulfil their respective tasks by essentially leaving them alone, baffled in the face of strange phenomena, which they nevertheless had to interpret and react to. Focusing foremost on medical experts in some form of state-service, the present essay seeks to map the power-relations of different parts of this distressing but exciting world, to which western culture’s perpetual fascination with vampirism owes its existence.'

As has so often been pointed out on this blog, despite western culture’s fascination with the subject very little has been written in English on the key events of 'vampire history', and for that reason it is very welcome to be able to point to the ’essay’ in question, which is in fact a M.A. thesis by one Adam Mezes. Supervised by Laszlo Kontler and Gabor Klaniczay, Mezes submitted his thesis, Insecure Boundaries: Medical experts and the returning dead on the Southern Habsburg borderland, at the Central European University History Department last year.

Situated in Budapest, Hungary, the History Department of the CEU according to its web site is 'the only transnational, English-language graduate school in Europe that is accredited both on the continent (in Hungary) and in the United States', it 'provides an excellent academic gateway to the history of Central, Southeastern, and Eastern Europe,' and 'offers one of the few programs in the world that effectively enables students to study comparatively the Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman Empires and their successor states, engaging with a variety of social, political, and cultural issues.' Its staff is multinational and multilingual, and among them we find Professor Laszlo Kontler who has a background in the European intellectual history of the early modern period and the Enlightenment. Kontler is the author of A History of Hungary: Millennium in Central Europe and the forthcoming Translations, Histories, Enlightenments: William Robertson in Germany, 1760-1795. Professor Klaniczay is affiliated with the Medieval Department of the CEU and author of, among many other papers and books, an influential article from 1987 on the Decline of Witches and Rise of Vampires in 18th Century Habsburg Monarchy that has featured prominently in the succeeding literature on 18th century witchcraft affairs.

In his thesis, Mezes focuses on the context of the vampire investigations of the 18th century, in particular those in Serbia (Kisiljevo and Medvedja) and those investigated by Georg Tallar in Banat and Oltenia. Briefly mentioning a few books on the subject, Mezes states that: 'It is visible from this brief literature overview that considerably more attention has been paid to the findings of the medical reports than to the authors themselves. The factors which influenced the way they constructed their own role and formulated their reports have not been researched in depth. Taking the studies mentioned last as a departing point, the present essay makes an attempt at applying a magnifying glass on this frontier-region and investigate the specific spheres of power and authority which shaped the formulation of the reports on vampirism. The exact mapping of these relations is a valid task, because much confusion exists even in the above mentioned literature dealing specificially with the topic of politics and vampires. It seems that basic, factual matters have to be cleared, otherwise the scholarly gaze on vampirism and state will remain hazy.'

Mezes is particularly interested in vampirism as 'a problem of ordering for Habsburg statecraft', because it was in the 18th century that various ways of governance and policing were explored and implemented in order to centralize and uniform the control of the authorities. In the borderland areas to the South, a direct control based on central institutions was employed, which had the effect that what was going on locally among the common people became more visible to the central authorities.

So Mezes describes the organization and development of the Militärgrenze, the military frontier in the Southeastern parts of Habsburg territory, including the military and governmental structure of Serbia in the short period that it was under Habsburg occupation. He also goes into detail with regards to the frontier's function as a plague cordon, the setting up of special quarantine stations where people were to be confined until one could be sure that they were not potential carriers of the plague miasma, and the order to report suspicious infection cases directly to the Aulic War Council.

Mezes correctly identifies Kisilova from Frombald's report with present day Kisiljevo, and points out the differences between Kisiljevo and Medvedja in the military and governmental structure of Serbia at the time. Kisiljevo being a cameral village, and not a Hayduk village like Medvedja, the investigations of purported cases of vampirism were handled differently in these two villages. Mezes also discusses the curious circumstances related to the copy of Frombald's manuscript and other information on the case in the Viennese archives.

All this is a nice and clear exposition and synthesis of information most of which can be found in various books on the subject and on the Militärgrenze, but that is certainly not the case when it comes to the part of the thesis on Georg Tallar. Here Mezes carries out a detailed analysis and comparison of both the printed book and the original manuscript to learn more about this 'enigmatic figure', Tallar, his investigation of vampire cases and the reason why a publisher decided to print the book some thirty years after the report was written.

Tallar was part of a commission consisting of himself, a theologian, and a physician, the latter according to Mezes possibly the Protomedicus Paul Adam Kömovesch (actually: Kômûves) who is recorded to having singlehandedly investigated one case of vampirism. Mezes suggests that, perhaps, the three did not actually work together, which could perhaps explain why it was Tallar and not the Protomedicus who wrote the report. On the other hand, Mezes notes that in the manuscript there are sections of a more religious character, which are so different from the otherwise sceptical voice of Tallar, that he thinks they may originate from the hand of the (unknown) theologian: 'Every now and then, there appears a voice in the text – albeit faintly and awkwardly – which addresses issues of demonic activity and morals and their consequences.'

These parts of the manuscript were omitted when the Viennese publisher Johann Georg Möβle prepared the text for printing. In his foreword Möβle claims that he stumbled upon the manuscript by accident, but Mezes finds this improbable.

Although dated 1756, Tallar may have written it in 1753: 'hypothetically, it might be conjectured, that Tallar handed in his report to the Banat Provincial Administration in 1753, right after he finished his investigation, just as his fellow-commissioner, Kömovesch did. Then, when the Hermsdorf-scandal popped out, the central administration wanted to collect materials about vampirism and asked the Banat Administration to send all documents they have on the issue. This scenario would explain why the report is dated 1756: it was written on it when the Aulic Treasury (Hofkammer) received the document three years after the report was actually finished.'

So what prompted Möβle to publish the report some thirty years later in 1784? Mezes convincingly conjectures that news of another vampire investigation got to Vienna that year, and that the authorities once again searched their archives for material on vampires, found Tallar's manuscript, and asked Möβle to publish it. Mezes lists a number of works published by Möβle that supports his theory that Möβle not only catered for 'the public's hunger for curiosities,' but was in fact also publishing books that would serve as instructive 'governmental messages.'

As for the vampire case that prompted the publication, Mezes writes: 'In our opinion (though again, further investigation is needed), the publication of the report has something to do with another vampire scandal, one which secondary literature does not yet know of (in fact neither do we). What points nevertheless in this direction is a royal statute of Joseph II., dates 1784.11.02., in which the king warns the Orthodox Church to take active part in the fight against vampire-beliefs.'

Mezes refers to an entry in Franz Xavier Linzbauer's voluminous Codex Sanitario-medicinalis Hungariae (a book that contains other source material on vampire investigations) concerning the practice among some people of the Orthodox faith of leaving corpses unburied ('in aperta tumba') for fear of bloodsuckers ('Wampier'), a practice that may cause epidemics illnesses to spread, so the authorites found it necessary to reiterate its stance.*

Apart from the theological omissions mentioned above, Mezes finds that Möβle was fairly loyal to the text of the manuscript, although he made some changes like removing Tallar's references to the local authorities that appointed him to the commission: 'By doing so, Möβle severed important roots which linked the report to its original circumstances, and at the same time managed to elevate the report to a more general level of the enlightenment fighting the forces of darkness, be they superstitions or illnesses.'

Obviously, this is highly interesting work, particularly on Tallar's investigations and the interest in vampires of the late 18th century Enlightenment. Certainly a well-written and well-researched thesis, it earned Mezes a Hanak Prize at the History Department of the CEU, and as it is written in English, it also offers those who are unable to read the German language literature on the subject a glimpse of what they are missing out on.

Thanks to Jonathan Ferguson for notifying me of this work.

*) The contemporary review of the printed edition of Tallar's report that I quoted in an earlier post, was published 'Wien am 17ten Hornung, 1784', i.e. in Vienna on February 17 1784, and if that is correct, Möβle published Tallar's report several months before the royal statute.

As has so often been pointed out on this blog, despite western culture’s fascination with the subject very little has been written in English on the key events of 'vampire history', and for that reason it is very welcome to be able to point to the ’essay’ in question, which is in fact a M.A. thesis by one Adam Mezes. Supervised by Laszlo Kontler and Gabor Klaniczay, Mezes submitted his thesis, Insecure Boundaries: Medical experts and the returning dead on the Southern Habsburg borderland, at the Central European University History Department last year.

Situated in Budapest, Hungary, the History Department of the CEU according to its web site is 'the only transnational, English-language graduate school in Europe that is accredited both on the continent (in Hungary) and in the United States', it 'provides an excellent academic gateway to the history of Central, Southeastern, and Eastern Europe,' and 'offers one of the few programs in the world that effectively enables students to study comparatively the Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman Empires and their successor states, engaging with a variety of social, political, and cultural issues.' Its staff is multinational and multilingual, and among them we find Professor Laszlo Kontler who has a background in the European intellectual history of the early modern period and the Enlightenment. Kontler is the author of A History of Hungary: Millennium in Central Europe and the forthcoming Translations, Histories, Enlightenments: William Robertson in Germany, 1760-1795. Professor Klaniczay is affiliated with the Medieval Department of the CEU and author of, among many other papers and books, an influential article from 1987 on the Decline of Witches and Rise of Vampires in 18th Century Habsburg Monarchy that has featured prominently in the succeeding literature on 18th century witchcraft affairs.

In his thesis, Mezes focuses on the context of the vampire investigations of the 18th century, in particular those in Serbia (Kisiljevo and Medvedja) and those investigated by Georg Tallar in Banat and Oltenia. Briefly mentioning a few books on the subject, Mezes states that: 'It is visible from this brief literature overview that considerably more attention has been paid to the findings of the medical reports than to the authors themselves. The factors which influenced the way they constructed their own role and formulated their reports have not been researched in depth. Taking the studies mentioned last as a departing point, the present essay makes an attempt at applying a magnifying glass on this frontier-region and investigate the specific spheres of power and authority which shaped the formulation of the reports on vampirism. The exact mapping of these relations is a valid task, because much confusion exists even in the above mentioned literature dealing specificially with the topic of politics and vampires. It seems that basic, factual matters have to be cleared, otherwise the scholarly gaze on vampirism and state will remain hazy.'

Mezes is particularly interested in vampirism as 'a problem of ordering for Habsburg statecraft', because it was in the 18th century that various ways of governance and policing were explored and implemented in order to centralize and uniform the control of the authorities. In the borderland areas to the South, a direct control based on central institutions was employed, which had the effect that what was going on locally among the common people became more visible to the central authorities.

So Mezes describes the organization and development of the Militärgrenze, the military frontier in the Southeastern parts of Habsburg territory, including the military and governmental structure of Serbia in the short period that it was under Habsburg occupation. He also goes into detail with regards to the frontier's function as a plague cordon, the setting up of special quarantine stations where people were to be confined until one could be sure that they were not potential carriers of the plague miasma, and the order to report suspicious infection cases directly to the Aulic War Council.

|

| Source: Wikimedia |

Mezes correctly identifies Kisilova from Frombald's report with present day Kisiljevo, and points out the differences between Kisiljevo and Medvedja in the military and governmental structure of Serbia at the time. Kisiljevo being a cameral village, and not a Hayduk village like Medvedja, the investigations of purported cases of vampirism were handled differently in these two villages. Mezes also discusses the curious circumstances related to the copy of Frombald's manuscript and other information on the case in the Viennese archives.

All this is a nice and clear exposition and synthesis of information most of which can be found in various books on the subject and on the Militärgrenze, but that is certainly not the case when it comes to the part of the thesis on Georg Tallar. Here Mezes carries out a detailed analysis and comparison of both the printed book and the original manuscript to learn more about this 'enigmatic figure', Tallar, his investigation of vampire cases and the reason why a publisher decided to print the book some thirty years after the report was written.

Tallar was part of a commission consisting of himself, a theologian, and a physician, the latter according to Mezes possibly the Protomedicus Paul Adam Kömovesch (actually: Kômûves) who is recorded to having singlehandedly investigated one case of vampirism. Mezes suggests that, perhaps, the three did not actually work together, which could perhaps explain why it was Tallar and not the Protomedicus who wrote the report. On the other hand, Mezes notes that in the manuscript there are sections of a more religious character, which are so different from the otherwise sceptical voice of Tallar, that he thinks they may originate from the hand of the (unknown) theologian: 'Every now and then, there appears a voice in the text – albeit faintly and awkwardly – which addresses issues of demonic activity and morals and their consequences.'

These parts of the manuscript were omitted when the Viennese publisher Johann Georg Möβle prepared the text for printing. In his foreword Möβle claims that he stumbled upon the manuscript by accident, but Mezes finds this improbable.

Although dated 1756, Tallar may have written it in 1753: 'hypothetically, it might be conjectured, that Tallar handed in his report to the Banat Provincial Administration in 1753, right after he finished his investigation, just as his fellow-commissioner, Kömovesch did. Then, when the Hermsdorf-scandal popped out, the central administration wanted to collect materials about vampirism and asked the Banat Administration to send all documents they have on the issue. This scenario would explain why the report is dated 1756: it was written on it when the Aulic Treasury (Hofkammer) received the document three years after the report was actually finished.'

So what prompted Möβle to publish the report some thirty years later in 1784? Mezes convincingly conjectures that news of another vampire investigation got to Vienna that year, and that the authorities once again searched their archives for material on vampires, found Tallar's manuscript, and asked Möβle to publish it. Mezes lists a number of works published by Möβle that supports his theory that Möβle not only catered for 'the public's hunger for curiosities,' but was in fact also publishing books that would serve as instructive 'governmental messages.'

As for the vampire case that prompted the publication, Mezes writes: 'In our opinion (though again, further investigation is needed), the publication of the report has something to do with another vampire scandal, one which secondary literature does not yet know of (in fact neither do we). What points nevertheless in this direction is a royal statute of Joseph II., dates 1784.11.02., in which the king warns the Orthodox Church to take active part in the fight against vampire-beliefs.'

Mezes refers to an entry in Franz Xavier Linzbauer's voluminous Codex Sanitario-medicinalis Hungariae (a book that contains other source material on vampire investigations) concerning the practice among some people of the Orthodox faith of leaving corpses unburied ('in aperta tumba') for fear of bloodsuckers ('Wampier'), a practice that may cause epidemics illnesses to spread, so the authorites found it necessary to reiterate its stance.*

|

| Franciscus Xav. Linzbauer: Codex Sanitario-Medicinalis Hungariae Tomus III. Sectio I, p. 122 (Buda, 1853) |

Obviously, this is highly interesting work, particularly on Tallar's investigations and the interest in vampires of the late 18th century Enlightenment. Certainly a well-written and well-researched thesis, it earned Mezes a Hanak Prize at the History Department of the CEU, and as it is written in English, it also offers those who are unable to read the German language literature on the subject a glimpse of what they are missing out on.

Thanks to Jonathan Ferguson for notifying me of this work.

*) The contemporary review of the printed edition of Tallar's report that I quoted in an earlier post, was published 'Wien am 17ten Hornung, 1784', i.e. in Vienna on February 17 1784, and if that is correct, Möβle published Tallar's report several months before the royal statute.

Labels:

Adam Mezes,

Banat,

Central European University,

Frombald,

Hermersdorf,

Johann Georg Möβle,

Joseph II,

Kisiljevo,

Klaniczay,

Kömovesch,

Laszlo Kontler,

Medvedja,

Militärgrenze,

plague,

Serbia,

Tallar

Monday, 17 March 2014

Peter Plogojowitz unearthed

The extraordinary Terra X documentary Dracula: Die wahre Geschichte der Vampire, that aired on German ZDF in October last year, is now available on Blu-ray in both 3D and 2D. Although primarily a gimmick, the 3D works reasonably well, e.g. in the Prunksaal of the Austrian National Library. As a bonus, the disc includes a National Geographic documentary on the archaeological find of Irish 'vampire skeletons'.

Both documentaries are readily available on youtube, where another interesting Terra X documentary can currently be found: Draculas Schatten: Fahndung im Reich der Finsternis from 1995, which includes a retellinig of the Peter Plogojowitz/Petar Blagojewic incident and an interview with Dr. Christian Reiter who talks about anthrax as the possible cause of the deaths in Kisiljevo.

Both documentaries are readily available on youtube, where another interesting Terra X documentary can currently be found: Draculas Schatten: Fahndung im Reich der Finsternis from 1995, which includes a retellinig of the Peter Plogojowitz/Petar Blagojewic incident and an interview with Dr. Christian Reiter who talks about anthrax as the possible cause of the deaths in Kisiljevo.

Sunday, 2 February 2014

In Styria ...

'In Styria ...' Irishman Sheridan Le Fanu set his Carmilla in Styria, part of current day Austria. A current exhibition at the GrazMuseum in Graz in Styria now explores the role of Styria in vampire literature, the development of the media vampire, and what it is all about.

Le Fanu appears to have read an 1836 travel book, Schloss Hainfeld, or a Winter in Lower Styria by Basil Hall, and probably found the description of a pre-industrial and romantic part of Europe an appropriate setting for his vampire novella. By the time Bram Stoker was working on Dracula, he also chose Styria as the home of the vampire count, before deciding to place Count Dracula's castle in Transylvania. The curators of the GrazMuseum believe that at the end of the nineteenth century the construction of a backwards, threatening, and superstitious East Europe had moved further to the Southeast, making Styria a region less likely for a vampire story. Stoker, however, as we know, still retained Styria as a location in his short story Dracula's Guest.

The exhibition, Carmilla, der Vampir und wir (Carmilla, the vampire and us), sees the fictional vampire of Le Fanu and Stoker not only as an extension of the Romantic vampire figure, but rather as a reaction to the industrialization that changed the face of many West European countries throughout the nineteenth century. This is, of course, evident in the conflict between East and West in Dracula, but as industries, media, and the globalization has developed and transforms even remote places, the vampire becomes (in the view of the curators) more a mirror image of the problems that humans face in an everchanging world more and more out of contact with its history and roots. At the same time the vampire of fiction, just like humans, faces his (or her) own existential crisis.

The exhibition at the GrazMuseum appears to explore such themes rather than the vampire's roots in folk beliefs. It consists of five rooms, glimpses of which can be seen in a clip from Austrian TV, from which a few shots are shown below. It is open until Halloween this year, and a publication related to the exhibition will be available later this year.

Le Fanu appears to have read an 1836 travel book, Schloss Hainfeld, or a Winter in Lower Styria by Basil Hall, and probably found the description of a pre-industrial and romantic part of Europe an appropriate setting for his vampire novella. By the time Bram Stoker was working on Dracula, he also chose Styria as the home of the vampire count, before deciding to place Count Dracula's castle in Transylvania. The curators of the GrazMuseum believe that at the end of the nineteenth century the construction of a backwards, threatening, and superstitious East Europe had moved further to the Southeast, making Styria a region less likely for a vampire story. Stoker, however, as we know, still retained Styria as a location in his short story Dracula's Guest.

The exhibition, Carmilla, der Vampir und wir (Carmilla, the vampire and us), sees the fictional vampire of Le Fanu and Stoker not only as an extension of the Romantic vampire figure, but rather as a reaction to the industrialization that changed the face of many West European countries throughout the nineteenth century. This is, of course, evident in the conflict between East and West in Dracula, but as industries, media, and the globalization has developed and transforms even remote places, the vampire becomes (in the view of the curators) more a mirror image of the problems that humans face in an everchanging world more and more out of contact with its history and roots. At the same time the vampire of fiction, just like humans, faces his (or her) own existential crisis.

The exhibition at the GrazMuseum appears to explore such themes rather than the vampire's roots in folk beliefs. It consists of five rooms, glimpses of which can be seen in a clip from Austrian TV, from which a few shots are shown below. It is open until Halloween this year, and a publication related to the exhibition will be available later this year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+GrazMuseum.jpg)