Whether I first learned of Vlad the Impaler from reading some newspaper article or from watching the Swedish TV documentary Vem var Dracula? (Who was Dracula?, internationally known as In Search of Dracula), I am not sure. In any case, from a very young age I was aware of the supposedly 'historical origins' of Count Dracula, the vampire. Of course, McNally and Florescu did not come up with this idea when they published their bestselling In Search of Dracula, as one e.g. finds a reference to 'Voivode Drakula or Dracula, who ruled in Walachia in 1455-1462' in Harry Ludlam's Stoker biography from 1962, but it was their book that internationally established 'historical Dracula', Vlad Tepes, as a 'historical fact'.

|

| The Romanian stamp indicates the size of the book. |

Dieter Harmening's Der Anfang von Dracula. Zur Geschichte von Geschichte, published a decade later, on the other hand encourages the reader to follow in the footsteps of the historian reading source texts on the Impaler, as well as looking for the link between Vlad the Impaler and Count Dracula, the vampire.

This approach can now be carried out in full from your desk with the publication of the first of a three volume set Corpus Draculianum edited by Thomas M. Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe and Albert Weber, that collects all major sources for the life and deeds of Vlad the Impaler. The first volume is actually number 3, which collects sources from Ottoman world, written by both Muslim and Post-Byzantine Christian authors and as a whole complementing the more well-known European view of the Impaler with an Oriental Dracula figure.

The texts are mainly first and second hand sources, with only a few of the most important tertiary sources added. The primary sources were written by people who had been involved in Sultan Mehmed II's campaign against Vlad Tepes in 1462. Among them, Enveri has himself apparently seen many impaled corpses in Wallachia: 'Als jener abgezogen war, sahen wir dort viele Leichen/Auf den Pfähl [gezogen], manche alt, manche neu.'

The focus of most texts is the campaign, and some of the authors seem to have little knowledge of what happend to the Impaler after his escape to Hungary. Tursun Beg, one of the more well-known Ottoman authors, even believed that Vlad Tepes died in captivity in Hungary, his soul ending up in Hell: 'Die Ungarn nahmen ihn fest und kerkerten ihn ein. Und hier schickte er seine Seele in die Hölle.'

The Ottoman Dracula figure retains its own character until the 17th century, when it gradually takes on the shape of the Vlad the Impaler from the European tradition, that is reflected in e.g. the stories recounted by McNally and Florescu in their In Search of Dracula.

Each text in the Corpus is presented in the original language along with a German translation. Extensive notes are supplied to make the text easier to understand and appreciate, just as information on the authors, their motivations, the sources themselves and secondary literature accompany each text. Furthermore, a chronology of events and an index of names and places are included along with a minute analysis of the interrelation between the texts.

Although, no doubt only a specialist can genuinely appreciate and critically evaluate a work of this kind, I am confident that this volume provides invaluable information for the specialist and historian interested in Vlad the Impaler or in the history of the region during this period. The layman interested in uncovering the bare bones behind the recreation of historical events that have become associated with a popular figure of modern cultural history, will no doubt find it intriguing to witness 'history in the making'.

The other two volumes will folow within the next ear or two, and I am also told that Bohn, Gheorge, and Weber hope to present the Corpus in English later on.

In connection with the publication of the Corpus Draculianum, Professor Bohn is organizing a conference about Vlad Dracula later this year: Vlad Dracula - Tyrann oder Volkstribun? Historische Reizfiguren im Donau-Balkan-Raum:

'Vlad III. Ţepeş „Dracula“ ist durch eine Reihe von Gräueltaten im historischen Gedächtnis verankert. Das aus einer zeitgenössischen Rufmordkampagne resultierende Image rekurrierte vor allem auf seine vermeintliche despotische Blutrünstigkeit. Im Pantheon des rumänischen Geschichtsdenkens erwarb er sich hingegen einen Heldenplatz, da er die Auseinandersetzung mit Mehmed II., dem Eroberer Konstantinopels, gesucht hatte. Osmanische Chroniken schildern Vlad aber als ungläubigen und tyrannischen Rebellen, der unschädlich gemacht werden musste, um eine Pax Ottomana im europäischen Südosten herbeiführen und legitimieren zu können. Zwischen den Zeilen kristallisiert sich aus den Quellen jedoch auch das Bild eines Kreuzritters oder Volkstribunen heraus. Dass Vlad letztlich von Ungarn, Sachsen und Bojaren verraten wurde, machte deren moralische Argumentationsstrategien obsolet und erleichterte es der späteren rumänischen Nationalhistoriographie, ihren Heroen zu idealisieren. Bis heute verfügt die Forschung über keine nach zeitgemäßen wissenschaftlichen Kriterien verfasste Biographie des Vlad Ţepeş oder eine eingehende Aufarbeitung der späteren Erinnerungskulturen und historiographischen Debatten über ihn.

Gerade die Vita des Vlad Ţepeş bietet sich an, um über verschiedenartige kulturelle Prägungen charismatischer Herrscherpersönlichkeiten in Südosteuropa während des Spätmittelalters und in der frühen Neuzeit nachzudenken. Die Tagung soll deshalb in einer Vergleichsperspektive die komplexen Lebensläufe auch anderer Herrscher sowie die damals und heute damit verknüpften Erinnerungskulturen in den Blick nehmen. Übergreifend sollen Einblicke in eine große Zone der geschichtlichen Verflechtungen zwischen Ostmitteleuropa und dem Osmanischen Reich ermöglicht werden.

Anlass der Tagung ist die dreibändige Dokumentation „Corpus Draculianum“, deren erster Teil in Kürze von Thomas Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe und Albert Weber bei Harassowitz in Wiesbaden veröffentlicht wird.

Konferenzsprachen sind deutsch und englisch. Die Manuskripte der Vorträge sollen den Organisatoren zu Beginn der Tagung vorliegen und werden später in einem Sammelband publiziert.'

Corpus Dralianum 3. Die Überlieferung aus dem Osmanischen Reich costs € 68, and can be purchased directly from the publishers, Harassowitz Verlag.

|

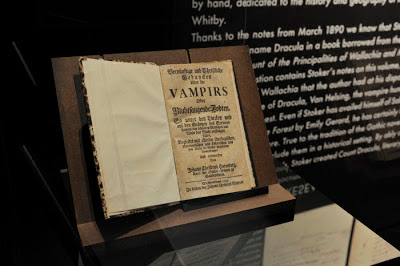

| Ottoman booty from the 16th century collected at Castle Ambras, Innsbruck |