On several occasions, particularly on the periphery of the Habsburg Empire during the 17th and 18th centuries, dead people were suspected of being revenants or vampires, and consequently dug up and destroyed. Some contemporary authors named this phenomenon Magia Posthuma. This blog is dedicated to understanding what happened and why.

Monday, 30 January 2012

Ashes to ashes

Learned people in the 17th and 18th century knew that corpses can be fully or partially preserved for a long period. Some three hundred years later, the processes involved in decomposition are still a matter of research, as this German documentary shows. The background is the problem of corpses not decomposing in the cemeteries as fast as necessary, and the aim is to speed up the process 'ashes to ashes, dust to dust'...

Saturday, 28 January 2012

Medieval ghostly encounters

The documentary on 'vampire skeletons' in the previous post refers to William of Malmesbury's tale of the witch from Berkeley and other medieval stories of ghosts and revenants. The best starting point for reading some of these stories is probably Andrew Joynes' Medieval Ghost Stories, originally published in 2001 and reprinted as a paperback a couple of times: 'a collection of ghostly encounters from medieval romances, monastic chronicles, sagas and heroic poetry.'

One slightly frustrating thing about this book, though, is that it opens with the interesting quote:

'... The ghost is not simply a dead or missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life...'

because when you look up the book that it is taken from, Avery F. Gordon's Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (1977), to learn more, the book really has little to say about the kind of ghosts and revenants one would expect, as it is really about 'haunting' in a more metaphorical sense, cf. Amazon's description: Gordon 'uses the metaphor of haunting to reflect on how contemporary society hides from its past.'

One slightly frustrating thing about this book, though, is that it opens with the interesting quote:

'... The ghost is not simply a dead or missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life...'

because when you look up the book that it is taken from, Avery F. Gordon's Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (1977), to learn more, the book really has little to say about the kind of ghosts and revenants one would expect, as it is really about 'haunting' in a more metaphorical sense, cf. Amazon's description: Gordon 'uses the metaphor of haunting to reflect on how contemporary society hides from its past.'

Friday, 27 January 2012

'Vampire Skeletons'

As reviewed on Taliesin meets the Vampires, and including a dramatization of Flückinger's examination of supposed vampires in Medvedja in 1732.

Monday, 16 January 2012

Bulgarian undead

Writing recently of Jordi Ardanuy, it is worth mentioning the quarterly journal L'Upir which frequently publishes articles by Ardanuy. Although written in Catalan, those of us who cannot read the language may still get something from looking at it anyway.

The December 2011 issue was recently distributed and focuses on vampires in Bulgaria. It includes an article by Ardanuy that a.o. deals with a 'vampire case' from Tirnova in Bulgaria mentioned by Rob Brautigam on his Shroudeater site:

'The corpses (who are refered to as witches) were rising from their graves after sunset. Just like some of the vampires that we know from Romania, they would spoil the food, mess up people's belongings and - remaining invisible - throw dirt and stones at people. They knocked people down and sat on them. Some of the people were so scared that they decided to leave the town.

An exorcist called Nikola was called to the rescue and was offered the price of 800 Kurus to do his job. Apparently he used a stick with a picture (possibly a Saint ?) on it to locate the troublesome graves. He found two of them. Both graves contained the bodies of soldiers that had been Yeniceri (better known in our part of the world as Yanitsaries or Janitsaries). The graves were opened and the corpses looked inflated, with hair and nails that had grown. Nikola decided that a stake should be driven through the stomach, the heart should be cut out and boiled. And then - for good measure and just to make sure - the bodies would have to be cremated.'

The December 2011 issue was recently distributed and focuses on vampires in Bulgaria. It includes an article by Ardanuy that a.o. deals with a 'vampire case' from Tirnova in Bulgaria mentioned by Rob Brautigam on his Shroudeater site:

'The corpses (who are refered to as witches) were rising from their graves after sunset. Just like some of the vampires that we know from Romania, they would spoil the food, mess up people's belongings and - remaining invisible - throw dirt and stones at people. They knocked people down and sat on them. Some of the people were so scared that they decided to leave the town.

An exorcist called Nikola was called to the rescue and was offered the price of 800 Kurus to do his job. Apparently he used a stick with a picture (possibly a Saint ?) on it to locate the troublesome graves. He found two of them. Both graves contained the bodies of soldiers that had been Yeniceri (better known in our part of the world as Yanitsaries or Janitsaries). The graves were opened and the corpses looked inflated, with hair and nails that had grown. Nikola decided that a stake should be driven through the stomach, the heart should be cut out and boiled. And then - for good measure and just to make sure - the bodies would have to be cremated.'

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Wednesday, 11 January 2012

Non-linearity and reanimation

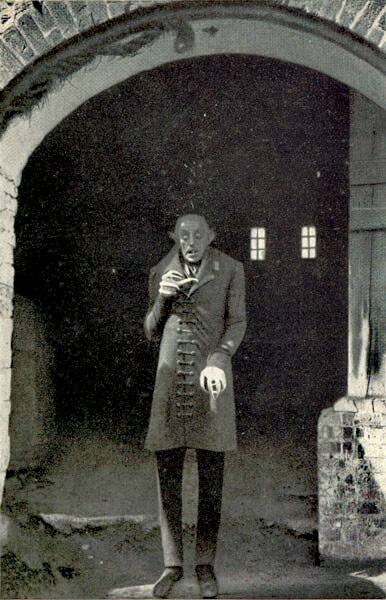

In 1922, the year Murnau's Nosferatu was released, critic and writer Béla Balázs wrote in the Viennese newspaper The Day:

'But crucially, film is a fundamentally new kind of art of an emerging new culture ... A means of mental expression that will influence humankind so widely and so deeply due to the unlimited accessibility of its technology must be of similar significance as Gutenberg's technological invention was for its time. Victor Hugo once wrote that the printed book assumed the role of the medieval cathedrals. The book became the carrier of the people's spirit and shredded it into millions of little opinions. The book broke the stone: the one church into a thousand books. Visible spirit became readable spirit, visual culture became conceptual. We probably need to say no more about how this changed the face of human society.

But today, another machine is at work to give human society a new spiritual shape. The many millions of people who sit every night and watch images, wordless images, which represent human feelings and thoughts - these many millions of people are learning a new language: the long forgotten, now newly emerging (and indeed international) language of facial expressiveness ... Perhaps we are standing on the threshold of a new visual culture?'

Bettina Bildhauer quotes Balázs in her 2011 book Filming the Middle Ages and comments: 'In a nutshell, we have the main themes here that recur in films and media theories to the present day. Balázs orders history into three periods, divided by the invention of the printing press and of film: the Middle Ages, characterized by the cathedral; the modern period, characterized by the book; and a new period characterized by film. For him, as for many medieval films, film and cathedral have more in common with each other than with the book: they are both visual and collective media, communicating through images to a united people, as opposed to the book, which communicates through words to individuals, having torn apart their communal spirit.' (p. 215)

She, however, points to another aspect of cinema and cathedrals that Balázs 'does not state explicitly, but on which his comparison is based: they both upset the fundamental idea that history is a linear progression, that time's arrow moves unstoppably, steadily and irreversibly forward in a line. By returning to the past, film resists a linear forward trajectory: the future, according to Balász's prediction, will circle back to the past.' (p. 215)

She traces these notions to the humanists of the mid-fourteenth century: 'The idea that time in the Middle Ages was not yet perceived in terms of linear progression originates from the very fact that the humanists declared themselves different from all that came before, thereby evidencing and fostering a sense of historical progress and change. The Romantics in the late eighteenth century were the first to argue for a New Middle Ages, revalued more positively as a model to cure the ills of modern society.' (p. 221)

Obviously, medieval film in Bildhauer's sense is not about historical accuracy, but rather 'a state of mind': 'a group of films usually set in the Middle Ages, creating non-linear time structures, playing visuality off against writing, and critiquing the modern individual human subject.' (p. 213)

The non-linear temporal aspect according to Bildhauer is evident in the reanimation of the dead in these films, which serves as the subject of the second chapter of her book, specifically considering the films Golem, Hard to Be a God, Waxworks, The Seventh Seal and Siegfried:

'In historiography, haunting has become a dominant, even clichéd metaphor for the relationship between present and past. In medieval film reanimation, rather than haunting, is used to depict the presence of the dead and its affective consequences. The dead return not so much as immaterial ghosts but as animated, solid or at least visible bodies. In the magical realist mode of many medieval films, the reality of the dead and of death is visualized on the diegesis through magically reanimated corpses or statues or through personifications of Death. (---) Alongside reanimation, a second frequently used visualization of the presence of the dead is that they physically approach the living, often in the direction of the camera and sometimes even stepping outside the diegesis. In the commonsensical concept of time as progressing in a linear and irreversible fashion, people and events seem less significant and have less power to affect us emotionally if they lived or took place a long time ago. The past, understood as severed and safely removed from the present, can gradually be forgotten and 'put in perspective'; and the dead, who are consigned to the past and referred to in the past tense, recede into the distance. The dead in medieval film reverse the usual movement of retreating into the past.' (p. 52)

Filming the Middle Ages is published by Reaktion Books.

'But crucially, film is a fundamentally new kind of art of an emerging new culture ... A means of mental expression that will influence humankind so widely and so deeply due to the unlimited accessibility of its technology must be of similar significance as Gutenberg's technological invention was for its time. Victor Hugo once wrote that the printed book assumed the role of the medieval cathedrals. The book became the carrier of the people's spirit and shredded it into millions of little opinions. The book broke the stone: the one church into a thousand books. Visible spirit became readable spirit, visual culture became conceptual. We probably need to say no more about how this changed the face of human society.

But today, another machine is at work to give human society a new spiritual shape. The many millions of people who sit every night and watch images, wordless images, which represent human feelings and thoughts - these many millions of people are learning a new language: the long forgotten, now newly emerging (and indeed international) language of facial expressiveness ... Perhaps we are standing on the threshold of a new visual culture?'

Bettina Bildhauer quotes Balázs in her 2011 book Filming the Middle Ages and comments: 'In a nutshell, we have the main themes here that recur in films and media theories to the present day. Balázs orders history into three periods, divided by the invention of the printing press and of film: the Middle Ages, characterized by the cathedral; the modern period, characterized by the book; and a new period characterized by film. For him, as for many medieval films, film and cathedral have more in common with each other than with the book: they are both visual and collective media, communicating through images to a united people, as opposed to the book, which communicates through words to individuals, having torn apart their communal spirit.' (p. 215)

She, however, points to another aspect of cinema and cathedrals that Balázs 'does not state explicitly, but on which his comparison is based: they both upset the fundamental idea that history is a linear progression, that time's arrow moves unstoppably, steadily and irreversibly forward in a line. By returning to the past, film resists a linear forward trajectory: the future, according to Balász's prediction, will circle back to the past.' (p. 215)

She traces these notions to the humanists of the mid-fourteenth century: 'The idea that time in the Middle Ages was not yet perceived in terms of linear progression originates from the very fact that the humanists declared themselves different from all that came before, thereby evidencing and fostering a sense of historical progress and change. The Romantics in the late eighteenth century were the first to argue for a New Middle Ages, revalued more positively as a model to cure the ills of modern society.' (p. 221)

Obviously, medieval film in Bildhauer's sense is not about historical accuracy, but rather 'a state of mind': 'a group of films usually set in the Middle Ages, creating non-linear time structures, playing visuality off against writing, and critiquing the modern individual human subject.' (p. 213)

The non-linear temporal aspect according to Bildhauer is evident in the reanimation of the dead in these films, which serves as the subject of the second chapter of her book, specifically considering the films Golem, Hard to Be a God, Waxworks, The Seventh Seal and Siegfried:

'In historiography, haunting has become a dominant, even clichéd metaphor for the relationship between present and past. In medieval film reanimation, rather than haunting, is used to depict the presence of the dead and its affective consequences. The dead return not so much as immaterial ghosts but as animated, solid or at least visible bodies. In the magical realist mode of many medieval films, the reality of the dead and of death is visualized on the diegesis through magically reanimated corpses or statues or through personifications of Death. (---) Alongside reanimation, a second frequently used visualization of the presence of the dead is that they physically approach the living, often in the direction of the camera and sometimes even stepping outside the diegesis. In the commonsensical concept of time as progressing in a linear and irreversible fashion, people and events seem less significant and have less power to affect us emotionally if they lived or took place a long time ago. The past, understood as severed and safely removed from the present, can gradually be forgotten and 'put in perspective'; and the dead, who are consigned to the past and referred to in the past tense, recede into the distance. The dead in medieval film reverse the usual movement of retreating into the past.' (p. 52)

Filming the Middle Ages is published by Reaktion Books.

Monday, 9 January 2012

Tricky problems

'There are several tricky problems inherent in discussing the earliest substantial manifestations of a much-loved screen genre,' David Pirie wrote in The Vampire Cinema (Hamlyn, 1977), which I purchased all those years ago as a teenager who had just become passionately interested in everything to do with vampires (when I had finally saved the DKK 64,90 necessary to buy the book, the bookshop had only one copy left). Pirie does not mention Le Manoir du Diable AKA The Haunted Castle or The Devil's Castle directed by Georges Méliès as the 'first' vampire film, but many books do, like John L. Flynn's Cinematic Vampires: The Living Dead on Film and Television, from The Devil's Castle (1896) to Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992) (McFarland, 1992): 'The imaginative climax occurs when the bat is vaporized in a puff of smoke, and from that puff of smoke, the vampire film was born.'

Thanks to youtube, the film itself is currently available for your own, personal judgment. Although the short film is imaginative and extremely well-made, I find that the vampire is, so to speak, in the eye of the beholder. Clearly, it contains elements that would reappear in vampire films, but I personally would not call it a vampire film.

If you are intrigued by this early film and you are not familiar with other films by Méliès, I encourage you to take a look at some of the other ones available on youtube, particularly his most famous one, Le Voyage dans la lune.

Thanks to youtube, the film itself is currently available for your own, personal judgment. Although the short film is imaginative and extremely well-made, I find that the vampire is, so to speak, in the eye of the beholder. Clearly, it contains elements that would reappear in vampire films, but I personally would not call it a vampire film.

If you are intrigued by this early film and you are not familiar with other films by Méliès, I encourage you to take a look at some of the other ones available on youtube, particularly his most famous one, Le Voyage dans la lune.

Sunday, 8 January 2012

A centenary

This year marks the centenary of Bram Stoker's death on April 20, and Constable who published Dracula back in 1897 has decided to celebrate the centenary with a facsimile of the first edition. Few people can afford a first edition, but this one is more reasonably priced, and is even available as a paperback. Published on April 5, the hardcover edition has a RRP of £50, and the paperback is available at a RRP of just £7.99. Both are available for pre-order at reduced prices from various internet dealers.

'A facsimile editon from the original publisher to celebrate the Centenary of Bram Stoker's death. No book since Mrs Shelley's Frankenstein, or indeed any other at all has come near yours in originality, or terror - Poe is nowhere...'-Charlotte Stoker (Mother of Bram Stoker).

Originally published in 1897, Bram Stoker's Dracula has spawned countless new editions, inspired over fifty films, and hundreds of reimaginings. The iconic and terrifying character of Stoker's imagination has permeated our conciousness in such away that Dracula is the seminal vampire of popular culture.

Set across London and into the darkest corners of Eastern Europe, Dracula is told through the journal entries and letters of its protagonists as they strive to survive the presence of Count Dracula in their lives. Young lawyer Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to assist in a land transaction, but finds himself trapped in the Count's castle, tormented by strange and unearthly occurrences. After a miraculous escape, he returns to England, only to find that the Count has followed him to London and has begun tracking his fiancé, Mina...

Reprinted in its original form, this edition of Dracula is perfect for a first time reader, or as a classic to keep forever.'

Various conferences and symposia mark the centenary, including:

The Bram Stoker Centenary Conference: Bram Stoker and Gothic Transformations at Whitby on April 12-14 with lectures by Christopher Frayling, Elizabeth Miller and Dacre Stoker.

Open Graves, Open Minds: Bram Stoker Centenary Symposium in Hampsted on April 20-21 with John Edgar Browning, Kim Newman, Dacre Stoker a.o.

Bram Stoker Centenary Conference 2012: Bram Stoker: Life and Writing at Trinity College in Dublin on July 5-6 with Christopher Frayling and Paul Murray.

Further events are listed here.

Stoker's death on the final page of the comic book Stoker biography Auf Draculas Spuren: Bram Stoker by Séra & Yves H. (Kult Editionen, 2007).

'A facsimile editon from the original publisher to celebrate the Centenary of Bram Stoker's death. No book since Mrs Shelley's Frankenstein, or indeed any other at all has come near yours in originality, or terror - Poe is nowhere...'-Charlotte Stoker (Mother of Bram Stoker).

Originally published in 1897, Bram Stoker's Dracula has spawned countless new editions, inspired over fifty films, and hundreds of reimaginings. The iconic and terrifying character of Stoker's imagination has permeated our conciousness in such away that Dracula is the seminal vampire of popular culture.

Set across London and into the darkest corners of Eastern Europe, Dracula is told through the journal entries and letters of its protagonists as they strive to survive the presence of Count Dracula in their lives. Young lawyer Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to assist in a land transaction, but finds himself trapped in the Count's castle, tormented by strange and unearthly occurrences. After a miraculous escape, he returns to England, only to find that the Count has followed him to London and has begun tracking his fiancé, Mina...

Reprinted in its original form, this edition of Dracula is perfect for a first time reader, or as a classic to keep forever.'

Various conferences and symposia mark the centenary, including:

The Bram Stoker Centenary Conference: Bram Stoker and Gothic Transformations at Whitby on April 12-14 with lectures by Christopher Frayling, Elizabeth Miller and Dacre Stoker.

Open Graves, Open Minds: Bram Stoker Centenary Symposium in Hampsted on April 20-21 with John Edgar Browning, Kim Newman, Dacre Stoker a.o.

Bram Stoker Centenary Conference 2012: Bram Stoker: Life and Writing at Trinity College in Dublin on July 5-6 with Christopher Frayling and Paul Murray.

Further events are listed here.

Stoker's death on the final page of the comic book Stoker biography Auf Draculas Spuren: Bram Stoker by Séra & Yves H. (Kult Editionen, 2007).

Jaw bones and carousing

One news story concerns an Italian archaeological find last autumn. In September 2011, the Daily Mail reported that during archaeological diggings in an ancient cemetery in Piombino in Tuscany, an 800 years old female skeleton was found with seven nails found driven through her jaw bone. Archaeologist Alfonso Forgione, from L'Aquila University, who led the dig said at the time:

'It's a very unusual discovery and at the same time fascinating. I have never seen anything like this before. I'm convinced because of the nails found in the jaw and around the skeleton the woman was a witch. She was buried in bare earth, not in a coffin and she had no shroud around her either, intriguingly other nails were hammered around her to pin down her clothes. This indicates to me that it was an attempt to make sure the woman even though she was dead did not rise from the dead and unnerve the locals who were no doubt convinced she was a witch with evil powers.'

As usual it is quite difficult to be certain what to make of the find, cf. my recent post on archaeological 'evidence' of vampire and revenant beliefs. News stories tend to be unreliable in these cases, so one should look out for what Forgione publishes on the matter.

An Italian actually plays a role in the aforementioned article on Danish funerary practices. This Italian visited Denmark in the 1620's and noted that when someone dies, the Danes do not grieve, they laugh, eat, drink and dance around the corpse. Apparently, when Denmark adopted the Lutheran faith, funerary practices changed, and people bid the deceased farewell by gathering socially for days. At times, they even gathered before the dying person had actually deceased.

When he or she had in fact died, the church bells chime to scare evil forces away. While the bells were chiming, the relations of the deceased notified the animals belonging to the deceased person of his or her death, so they would not accompany the deceased in death. News of the death were whispered into the ears of every animal, even the bees were informed as people gently knocked on the beehive.

Then the corpse was washed, dressed properly and put in a coffin. The feet, however, were kept without shoes to avoid the deceased from walking about, and as an extra precaution, the feet were tied together.

Over the next days, relatives and neighbours stopped by to participate in the wake. People sang, ate, played cards, drank beer and brandy, and danced until early morning.

In 1607, King Christian IV tried to prohibit the partying, but without success. A century later, pietist priests finally suppressed the carousing, promoting a more puritanical approach to death, so by the end of the 18th century all the partying was over. Nowadays, Danes usually participate in a service in a church or chapel followed by a sombre and relatively sober gathering, although named after the beer that is customarily imbibed: gravøl = grav (grave) + øl (beer).

The Danish history magazine is published by Bonnier Publications, and national versions are also published in the other Scandinavian countries, in Estonia, Latvia and in the Netherlands.

Saturday, 7 January 2012

Los vampiros

'Is this worth purchasing?' is a question I have asked myself many times over the years, when a new book title on vampires and related subjects turned up. Fortunately, with the internet one can sometimes find a reasonable amount of reviews and other information, but in many cases you are left to make a decision on the basis of almost no information at all. For that reason, over the years I have tried to write a bit about various books that might have some value for people with an interest in the subject of vampirism and posthumous magic along the lines of this blog.

Jordi Ardanuy is a physicist and vampire expert who has written extensively in Catalan and Spanish. Much of what he has written on the subject is available on the internet, cf. e.g. the web site of Cercle V, but I have been intrigued to see his book Los vampiros ¡vaya timo! published by Laetoli in 2009 in a series on superstition, pseudoscience and antisicence called ¡Vaya timo! aimed at teenagers and other younger readers. Other books in the series deal with e.g. witchcraft, tarot and psychoanalysis.

Ardanuy's book is short, containing only about 130 pages, and is no doubt easily read if you know Spanish. The first chapter deals with Lilith, lamiae, ghosts, incubi and efialtes, and the second contains annotated translations from Henry More and Valvasor on the shoemaker from Silesia, Johannes Cuntius, and Giure Grando. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 deal with the famous Serbian vampire cases, the 18th century debate on vampires, Van Swieten's commentaries, also drawing lines ahead to e.g. the vampire beliefs and traits in 19th century New England. Finally, chapters 6 and 7 are concerned with the fictional vampire and the modern conception of vampires.

So, overall it looks like it contains standard information the subject that can be found elsewhere. The main exception is probably a few pages dealing with the critical reaction of the Spanish benedictine monk Benito Jéronimo Feijoo to Dom Calmet's work on revenants and vampires. Although not frequently mentioned in books on vampires, Feijoo's critique of Calmet is touched upon in e.g. Fernando Vidal's paper Ghosts, the economy of religion, and the laws of princes. Dom Calmet's Treatise on the apparitions of spirits in Gespenster und Politik, edited by Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (Wilhelm Fink, 2007).

Ardanuy's list of recommended further reading is brief, mentioning works by Paul Barber, Jan Bondeson (a Spanish translation of his book on premature burial, Buried Alive), Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, and Jean Marigny, including only one Spanish book: Vampiros y hombres lobo by Erberto Petoia.

Jordi Ardanuy is a physicist and vampire expert who has written extensively in Catalan and Spanish. Much of what he has written on the subject is available on the internet, cf. e.g. the web site of Cercle V, but I have been intrigued to see his book Los vampiros ¡vaya timo! published by Laetoli in 2009 in a series on superstition, pseudoscience and antisicence called ¡Vaya timo! aimed at teenagers and other younger readers. Other books in the series deal with e.g. witchcraft, tarot and psychoanalysis.

Ardanuy's book is short, containing only about 130 pages, and is no doubt easily read if you know Spanish. The first chapter deals with Lilith, lamiae, ghosts, incubi and efialtes, and the second contains annotated translations from Henry More and Valvasor on the shoemaker from Silesia, Johannes Cuntius, and Giure Grando. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 deal with the famous Serbian vampire cases, the 18th century debate on vampires, Van Swieten's commentaries, also drawing lines ahead to e.g. the vampire beliefs and traits in 19th century New England. Finally, chapters 6 and 7 are concerned with the fictional vampire and the modern conception of vampires.

So, overall it looks like it contains standard information the subject that can be found elsewhere. The main exception is probably a few pages dealing with the critical reaction of the Spanish benedictine monk Benito Jéronimo Feijoo to Dom Calmet's work on revenants and vampires. Although not frequently mentioned in books on vampires, Feijoo's critique of Calmet is touched upon in e.g. Fernando Vidal's paper Ghosts, the economy of religion, and the laws of princes. Dom Calmet's Treatise on the apparitions of spirits in Gespenster und Politik, edited by Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (Wilhelm Fink, 2007).

Ardanuy's list of recommended further reading is brief, mentioning works by Paul Barber, Jan Bondeson (a Spanish translation of his book on premature burial, Buried Alive), Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, and Jean Marigny, including only one Spanish book: Vampiros y hombres lobo by Erberto Petoia.

Sunday, 1 January 2012

Wanbires on the front page

According to this weekly newspaper from March 1732, the Habsburg Emperor Charles VI found the news of the so-called 'Wanbieren', or Bloodsuckers, so curious and important, that the reports should be sent to the universities for evaluation. As we know, a lot was written on the subject over the next months and years, making the vampire a household name.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)