In 1922, the year Murnau's Nosferatu was released, critic and writer Béla Balázs wrote in the Viennese newspaper The Day:

'But crucially, film is a fundamentally new kind of art of an emerging new culture ... A means of mental expression that will influence humankind so widely and so deeply due to the unlimited accessibility of its technology must be of similar significance as Gutenberg's technological invention was for its time. Victor Hugo once wrote that the printed book assumed the role of the medieval cathedrals. The book became the carrier of the people's spirit and shredded it into millions of little opinions. The book broke the stone: the one church into a thousand books. Visible spirit became readable spirit, visual culture became conceptual. We probably need to say no more about how this changed the face of human society.

But today, another machine is at work to give human society a new spiritual shape. The many millions of people who sit every night and watch images, wordless images, which represent human feelings and thoughts - these many millions of people are learning a new language: the long forgotten, now newly emerging (and indeed international) language of facial expressiveness ... Perhaps we are standing on the threshold of a new visual culture?'

Bettina Bildhauer quotes Balázs in her 2011 book Filming the Middle Ages and comments: 'In a nutshell, we have the main themes here that recur in films and media theories to the present day. Balázs orders history into three periods, divided by the invention of the printing press and of film: the Middle Ages, characterized by the cathedral; the modern period, characterized by the book; and a new period characterized by film. For him, as for many medieval films, film and cathedral have more in common with each other than with the book: they are both visual and collective media, communicating through images to a united people, as opposed to the book, which communicates through words to individuals, having torn apart their communal spirit.' (p. 215)

She, however, points to another aspect of cinema and cathedrals that Balázs 'does not state explicitly, but on which his comparison is based: they both upset the fundamental idea that history is a linear progression, that time's arrow moves unstoppably, steadily and irreversibly forward in a line. By returning to the past, film resists a linear forward trajectory: the future, according to Balász's prediction, will circle back to the past.' (p. 215)

She traces these notions to the humanists of the mid-fourteenth century: 'The idea that time in the Middle Ages was not yet perceived in terms of linear progression originates from the very fact that the humanists declared themselves different from all that came before, thereby evidencing and fostering a sense of historical progress and change. The Romantics in the late eighteenth century were the first to argue for a New Middle Ages, revalued more positively as a model to cure the ills of modern society.' (p. 221)

Obviously, medieval film in Bildhauer's sense is not about historical accuracy, but rather 'a state of mind': 'a group of films usually set in the Middle Ages, creating non-linear time structures, playing visuality off against writing, and critiquing the modern individual human subject.' (p. 213)

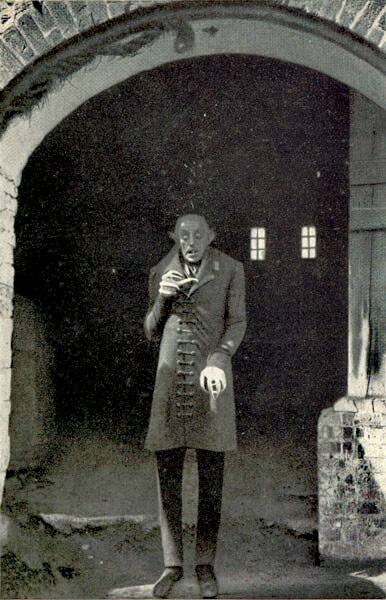

The non-linear temporal aspect according to Bildhauer is evident in the reanimation of the dead in these films, which serves as the subject of the second chapter of her book, specifically considering the films Golem, Hard to Be a God, Waxworks, The Seventh Seal and Siegfried:

'In historiography, haunting has become a dominant, even clichéd metaphor for the relationship between present and past. In medieval film reanimation, rather than haunting, is used to depict the presence of the dead and its affective consequences. The dead return not so much as immaterial ghosts but as animated, solid or at least visible bodies. In the magical realist mode of many medieval films, the reality of the dead and of death is visualized on the diegesis through magically reanimated corpses or statues or through personifications of Death. (---) Alongside reanimation, a second frequently used visualization of the presence of the dead is that they physically approach the living, often in the direction of the camera and sometimes even stepping outside the diegesis. In the commonsensical concept of time as progressing in a linear and irreversible fashion, people and events seem less significant and have less power to affect us emotionally if they lived or took place a long time ago. The past, understood as severed and safely removed from the present, can gradually be forgotten and 'put in perspective'; and the dead, who are consigned to the past and referred to in the past tense, recede into the distance. The dead in medieval film reverse the usual movement of retreating into the past.' (p. 52)

Filming the Middle Ages is published by Reaktion Books.

1 comment:

http://tv.yahoo.com/news/nicolas-cage--i-m-not-a-vampire.html Nicolas Cage seems a reanimated one!

Post a Comment