2014 marks the 250th anniversary of Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, usually celebrated as the first Gothic novel. The British Library will be celebrating the anniversary with an exhibition that opens on October 3 this year: Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination will be the most comprehensive exhibition on the subject in the UK so far:

'Beginning with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, this wide-ranging exhibition explores our enduring fascination with the mysterious, the terrifying and the awe-inspiring. It also examines the long shadow the Gothic imagination has cast across film, art, music, fashion, culture and our daily lives.

Gothic literature began as a challenge to the rational certainties of the Enlightenment. By exploring the harsh romance of the medieval past with its castles and abbeys, its wild landscapes and fascination with the supernatural, Gothic writers placed imagination firmly at the heart of their work.

Through over 200 rare exhibits including manuscripts, paintings, film clips and posters, Terror and Wonder explores all aspects of the Gothic world. Iconic works, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the sinister fairy tales of Angela Carter and the modern horrors of Clive Barker highlight the ways in which contemporary fears have been addressed by successive generations of Gothic writers. Paintings, films and even a vampire-slaying kit add colour and drama to the story.

Terror and Wonder promises to be beautiful, dark, inspiring and haunting. Step into this world, if you dare.'

The British Library web site already contains a theme on the subject, including, of course, a page on Dracula and vampire literature (incidentally, they also have a page on Emily Gerard's The Land beyond the Forest). They have also made a youtube video on the Gothic in which Professor John Bowen discusses Gothic motifs while wandering around Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill House.

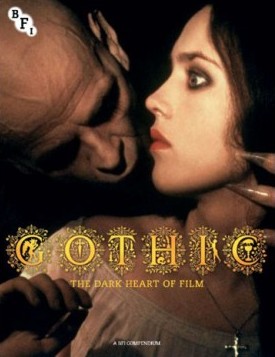

This exhibition follows hot on the heels of a Gothic film festival, Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film, arranged by the British Film Institute (BFI) in 2013. The BFI published a compendium, which is actually a delightful introduction to the world of Gothic film, its landscapes, architecture and inhabitants. In fact, this is probably one of the rare instances you will see me recommending a book on Gothic fiction on this blog, but the thematic approach to the subject as well as the host of experts who have contributed to it makes it a real treat, even for people with a more casual interest in the genre.

So the book includes essays on the relation between Gothic cinema and literature, architecture and art, with Martin Myrone, author of a nice book on Fuseli and contributor to the Tate exhibition on Gothic Nightmares back in 2006, noting that 'the relationship between the canon of Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase (c. 1760-1830) and the visual imagery of the same date is far from simple: the relationship of this early Gothic art and writing to modern cinema no more so.' Still, he later on concedes that 'nonetheless, there are parallels and resonances between Gothic literature of the 'classic' phase and precisely contemporary visual art, and between these and modern cinema,' accompanying his essay with a number of examples of these homologies, of which the most famous is, of course, Fuseli's Nightmare (see the Gothic Nightmares catalogue from Tate for numerous examples).

However many experts have contributed to the conpendium, they still are unable to solve the conundrum of pinning down what the Gothic 'genre' actually is. Myrone states that it is 'now often understood as, by definition, a trans-medial, genre-defying, migratory and polluting phenomenon, we should not expect homologies between Gothic productions in different media and eras need be predictable, explicit or orderly.' The paradox of how relatively easy it is to describe the Gothic 'landscape', while it seems almost impossible to define it, is what makes the compendium - cf. the title's nod to Joseph Conrad - a 'Grand Tour of the Gothic,' as Sir Christopher Frayling says in his foreword.