’… One of the most curious legacies ever bequeathed to anybody is perhaps that of £1000 left by the late Mrs Olivia Flint, of Pittsburg, to her doctor: Mrs Flint was very fond of novel reading, and, although very ill, began to read Bram Stoker’s thrilling romance, ”Dracula.” So interested did the dying woman become in it, that when she had read a chapter or two, she turned to her nurse, and, asking for pen and ink, wrote a few words to the effect that if Dr Allardyce could keep her alive long enough for her to finish the tale he was to receive a legacy of £1000. Mrs Flint lived for several hours after the last words had been read.’

This, an excerpt from the Marlborough Express Nov 2 1909, is one of the more curious examples of the early reception of Bram Stoker’s Dracula that have now been collected in a slim volume, Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Critical Feast. An annotated reference of early reviews and reactions, 1897-1913, compiled and annotated, with an introduction, by John Edgar Browning (Apocryphile Press, 179 pages, $18.95).

Aiming at both dispelling the misconception that Dracula received a mixing critical reception and providing literary scholars and the public with the documentation, Browning compiles 91 examples of reviews and letters, along with book covers and ads, from the English languaged part of the world where most of the initial editions were published. Only two translations appeared in Stoker’s lifetime, and a ‘bibliographical afterword’ by J. Gordon Melton presents of a list of non-English editions of Dracula.

The tale of a ‘human vampire’, as many reviewers call Count Dracula, is generally favourably received, and apparently made the blood of many critics curl. ‘We had thought that vampires were extinct,’ notes the Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, ‘but Mr. Bram Stoker has set himself to prove to us the contrary. Or rather he has recreated them with considerable ingenuity and a distinct gift for story-writing of the blood-curdling order.’ ‘There are a hundred nightmares in “Dracula,” and each is more uncanny than the last,’ writes St. James’ Gazette, while a reviewer in The Daily Mail is reminded of the author of a number of gothic novels: ‘It is said of Mrs. Radcliffe that, when writing her now almost forgotten romances, she shut herself up in absolute seclusion, and fed upon raw beef, in order to give her work the desired atmosphere of gloom, tragedy and terror. If one had no assurance to the contrary, one might well suppose that a similar method and regimen had been adopted by Mr. Bram Stoker while writing his new novel Dracula.’

Some critics found that the transition of the vampire from the more gothic Transylvanian setting to contemporary London did not work so well.‘Vampires need a Transylvanian background to be convincing,’ wrote The Academy: A Weekly Review of Literature, Science, and Art, adding: ‘The witches in “Macbeth” would not be effective in Oxford-Street.’ Still, there was no doubt that Dracula’s castle is not a place to visit, in the words of The Glasgow Herald: ‘Henceforth we shall wreathe ourselves in garlic when opportunity offers, and firmly decline all invitations to visit out-of-the-way clients in castles in the South-East of Europe. Dracula is a first rate book of adventure.’

What will strike modern day readers as odd, is that some critics saw Dracula as a werewolf book. ‘Mr. Bram Stoker, in his remarkable novel “Dracula”, has gone to the old legends of the were-wolf for the inspiration of his story,’ writes The Speaker, calling the novel ‘the first introduction of the were-wolf to English soil.’ Similarly, The Daily Telegraph finds that Bram Stoker illustrates and modernises ‘a revival of a mediaeval superstition, the old legend of the “were-wolf”,’ and traces this ‘old legend’ and its literature more closely, as the critic asks: ‘What has Mr. Bram Stoker been reading?’

Indeed, what has Stoker been reading? Today, we tend to forget how small the existing ‘canon’ of vampire literature in the English language was when Stoker wrote the novel. In fact, the deluge of books on the subject only dates back to the 1960’s or 1970’s, and the 'classics' by Ernest Jones, Dudley Wright and Montague Summers were all published after Stoker’s death. So in the 1890’s, one might have found the translations of Dom Calmet, Herbert Mayo’s letters, and a bit here and there, including the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould’s The Book of Werewolves, Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition from 1865, which is in fact mentioned by the reviewers of both The Daily Telegraph and The Stage, the latter apparently finding some pleasure in describing the horrors of the novel:

‘Those who know the Rev. S. Baring Gould’s little volume on the Were-Wolf, a theme also touched on here and there by Kipling, may possibly not be repelled by the grisly details of two beautiful and virtuous women having the veins in their throats sucked by the red lips, and lacerated by the gleaming white teeth of this centuries-old Transylvanian warrior and statesman, who often appears as a gaunt wolf and a huge bat.’

In his notes, Browning writes that the convention of seeing vampires transform into wolves ‘was to fin de siècle readers relatively unfamiliar – practically an innovation at the hands of Stoker.’ His other vampiric innovations are humourously commented on by Longman’s Magazine, when reviewing an inexpensive reissue in 1901: ‘The rules of vampirizing, as indicated by Mr. Stoker, are too numerous and too elaborate. One does not see why the leading vampire, Count Dracula, could not bolt out of the box where was finally run to earth by a solicitor named Jonathan. If he could fly about as a bat, why did he crawl down walls head foremost? The rules of the game of Vampire ought to be printed in appendix: at present the pastime is as difficult as Bridge.’ The reviewer then lays down eight chief rules like e.g. this sixth rule: ‘No vampire can vamp a person protected by garlic.’

Fortunately, an interview with Stoker himself was published in The British Weekly, allowing him to comment on both his sources and the vampire belief itself. Asked, ‘Is there any historical basis for the legend?’ he answers:

‘It rested, I imagine, on some such case as this. A person may have fallen into a death-like trance and been buried before the time. Afterwards the body may have been dug up and found alive, and from this a horror seized upon the people, and in their ignorance they imagined that a vampire was about. The more hysterical, through excess of fear, might themselves fall into trances in the same way; and so the story grew that one vampire might enslave many others and make them like himself. Even in the single villages it was believed that there might be many such creatures. When once the panic seized the population, their only thought was to escape.’

He apparently thought that the vampire belief was particularly prevalent in certain parts of Styria (where he originally set Dracula), and added, that ‘the legend is common to many countries, to China, Iceland, Germany, Saxony, Turkey, the Cersonese, Russia, Poland, Italy, France, and England, besides all the Tartar communities.’ Two sources are mentioned in the interview: Baring-Gould’s book and Emily Gerard’s Essays on Roumanian Superstitions.

Interestingly, not many reviewers go into detail regarding the subject of vampires. The National Observer, and British Review of Politics, Economics, Literature, Science, and Art, briefly mentions that ‘More awful even than the ghoul of the Arabian Nights is the Slavonic superstition of the human vampire, which, dead to all intent and purposes during the day, is supposed to prowl around by night and gorge itself with the blood of living man,’ adding that ‘this fearful legend, which flourished in Eastern Europe a century ago, and still finds credence among the ignorant.’ The Liverpool Mercury claims that it is ‘An old Eastern superstition, still having weight in Hungary.’

On the whole, the only reviewer to deal with ‘vampiredom’ in more detail is actually the one writing for the Australian Argus in 1897, who states that ‘Vampires – the “living dead,” whose corpses cannot decay, but who have the power of rising from their graves at night to batten upon the blood of human beings – are the Vroucolakas of the Greeks,' and then goes on to mention that 'They have been treated of by an old German writer, Michael Raufft (sic!), in his learned book “De Masticatione Mortuorum in Tumulis,” by the Frenchman Calmet, and by many another grave-faced sifter of mediæval superstitions,' before supplying more information about 'these unpleasant noctural prowlers.'

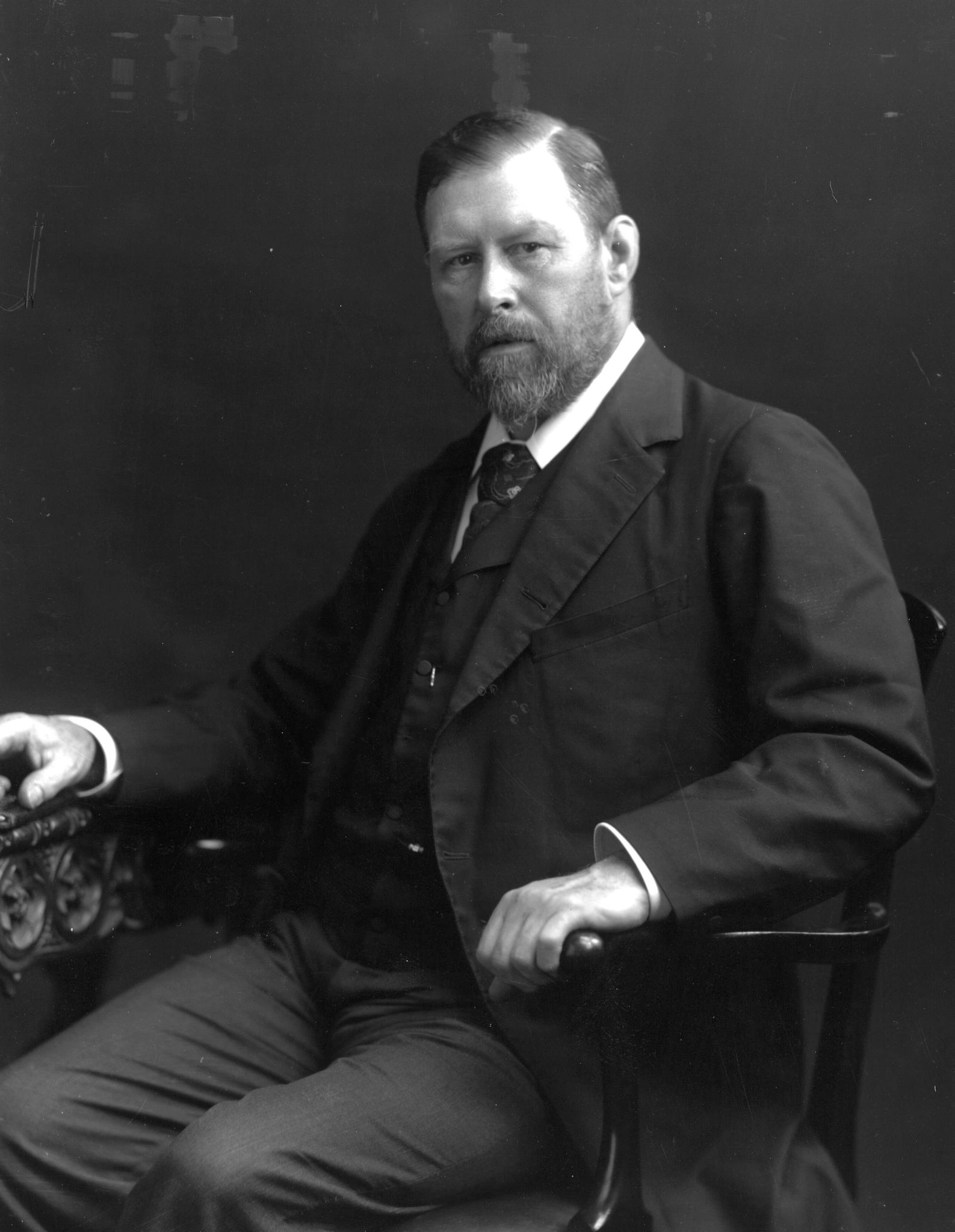

Upon Stoker’s death one hundred years ago on April 20 1912 , The Outlook found reason to note that ‘The lamented death of the author should direct fresh attention to the most imaginative creation of his pen. For weird force and picturesque horror Dracula deserves to rank with the classics of morbidity.’

For that reason, as well as for the novel's role in keeping ‘vampiredom’ alive and well in modern popular culture, the centenary of Stoker's death is good reason to read or re-acquaint oneself with the novel. For those interested in getting a better understanding of the literary reception of this, the single most important piece of vampire fiction, John Edgar Browning’s reference book is highly recommended.

Finally, a few words regarding the bibliography of translations: It is quite a daunting task to compile a complete and faultless bibliography of this task, and judging by the Scandinavian language editions mentioned, it is not a completely or a fully correct list. The Danish translations are all listed under the title ‘Drakula,’ but have actually all been titled Dracula, and I doubt that the list of adaptations is complete. The list of Swedish editions is, unfortunately, incomplete, and it is not correct that the first English translation of the preface to the Icelandic translation was published in 1993.

Sometime in the mid-Eighties, I was in contact with Richard Dalby, author of the first Stoker bibliography (published by the aptly named Dracula Press in 1983), and supplied him with information on the translation and copies of the preface. He subsequently had it translated and published by Guild Publishing in 1986 in a one-volume edition of both Dracula and The Lair of the White Worm, this also being the first time the latter novel was reprinted in its original length, as it had been absolutely butchered in all previous reprints.

2 comments:

To be fair on the Australian writer, 'Raufft' [Michael Ranfft] is likely derived from Calmet.

Not only is it spelt that way in English translations of his work - like The phantom world (1850) - but Calmet, himself, used 'Raufft' in his 1746 dissertation (cf.: Google Books).

Nonetheless, a great write-up as per usual, Niels.

In the days of handwritten manuscripts, no doubt 'u' and 'n' could easily get mixed up :-)

Post a Comment